Best I can do is

"\ude41🙂".split("").reverse().join("")

returns "\ude42🙁"

Post funny things about programming here! (Or just rant about your favourite programming language.)

Best I can do is

"\ude41🙂".split("").reverse().join("")

returns "\ude42🙁"

"🐈".concat() = "😼"":-)".reverse() == ")-:"

Close enough

but

"🙂".reverse() == "🙃"

JavaScript taking notes

You could implement that on a chat, but I wouldn't do that on a string

Where's your sense of adventure?!

[🌽].pop() == 🍿

"🚴".push() = "🚲🤸"Also, it should turn an error into an empty but successful call. /s

Calling reverse() on a function should return its inverse

isprime.reverse(True)

// outputs 19 billion prime numbers. Checkmate, atheists.It's a just a joke, but I feel like that actually says something pretty profound about duck typing, and how computable it actually is.

Be the operator overload you wish to see in the world

"☹️".reverse() == "☹️"wasn't it

🙁

.

r

e

v

e

r

s

e

()

You're no fun

Look closer at the beauty mark, I flipped the emoji

Then “b” backwards would have to be “d”

"E".reverse() == "∃"

Today I found out that this is valid JS:

const someString = "test string";

console.log(someString.toString());

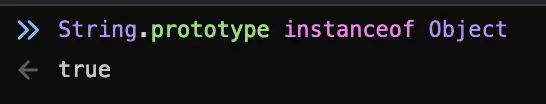

Everything that's an Object is going to either inherit Object.prototype.toString() (mdn) or provide its own implementation. Like I said in another comment, even functions have a toString() because they're also objects.

A String is an Object, so it's going to have a toString() method. It doesn't inherit Object's implementation, but provides one that's sort of a no-op / identity function but not quite.

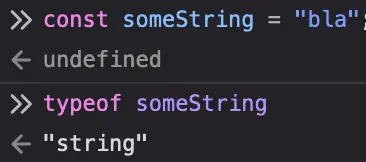

So, the thing is that when you say const someString = "test string", you're not actually creating a new String object instance and assigning it to someString, you're creating a string (lowercase s!) primitive and assigning it to someString:

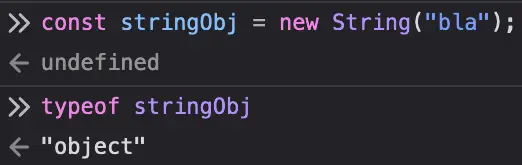

Compare this with creating a new String("bla"):

In Javascript, primitives don't actually have any properties or methods, so when you call someString.toString() (or call any other method or access any property on someString), what happens is that someString is coerced into a String instance, and then toString() is called on that. Essentially it's like going new String(someString).toString().

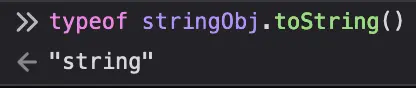

Now, what String.prototype.toString() (mdn) does is it returns the underlying string primitive and not the String instance itself:

Why? Fuckin beats me, I honestly can't remember what the point of returning the primitive instead of the String instance is because I haven't been elbow-deep in Javascript in years, but regardless this is what String's toString() does. Probably has something to do with coercion logic.

[This comment has been deleted by an automated system]

I dint know many OO languages that don’t have a useless toString on string types.

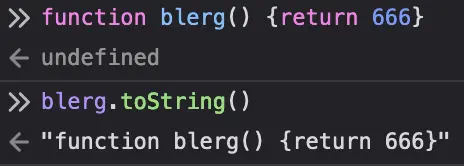

Well, that's just going to be one of those "it is what it is" things in an OO language if your base class has a toString()-equivalent. Sure, it's probably useless for a string, but if everything's an object and inherits from some top-level Object class with a toString() method, then you're going to get a toString() method in strings too. You're going to get a toString() in everything; in JS even functions have a toString() (the output of which depends on the implementation):

In a dynamically typed language, if you know that everything can be turned into a string with toString() (or the like), then you can just call that method on any value you have and not have to worry about whether it'll hurl at runtime because eg. Strings don't have a toString because it'd technically be useless.

I dint know many OO languages that don’t have a useless toString on string types

Okay, fair enough. Guess I never found about it because I never had to do it... JS also allows for "test string".toString() directly, not sure how it goes in other languages.

It's also incredibly useful as a failsafe in a helper method where you need the argument to be a string but someone might pass in something that is sort of a string. Lets you be a little more flexible in how your method gets called