this post was submitted on 03 Dec 2023

7 points (100.0% liked)

196

16401 readers

2230 users here now

Be sure to follow the rule before you head out.

Rule: You must post before you leave.

founded 1 year ago

MODERATORS

you are viewing a single comment's thread

view the rest of the comments

view the rest of the comments

In some countries we're taught to treat implicit multiplications as a block, as if it was surrounded by parenthesis. Not sure what exactly this convention is called, but afaic this shit was never ambiguous here. It is a convention thing, there is no right or wrong as the convention needs to be given first. It is like arguing the spelling of color vs colour.

It's The Distributive Law

No, it's an actual rule, and 1 is the only correct answer here - if you got 16 then you didn't obey the rule.

It's 2 actual rules of Maths - Terms and The Distributive Law.

Correct.

Yes there is - obeying the rules is right, disobeying the rules is wrong.

BDMAS bracket - divide - multiply - add - subtract

BEDMAS: Bracket - Exponent - Divide - Multiply - Add - Subtract

PEMDAS: Parenthesis - Exponent - Multiply - Divide - Add - Subtract

Firstly, don't forget exponents come before multiply/divide. More importantly, neither defines wether implied multiplication is a multiply/divide operation or a bracketed operation.

The Distributive Law says it's a bracketed operation. To be precise "expand and simplify". i.e. a(b+c)=(ab+ac).

Exponents should be the first thing right? Or are we talking the brackets in exponents..

Brackets are ALWAYS first.

Exponents are second, parentheses/brackets are always first. What order you do your exponents in is another ambiguity though.

No it isn't - top down.

2^3^4 is ambiguous. 2^(3^4) is standard practice, but some calculators aren't that smart and will do (2^3)^4.

It's ambiguous because it works both ways, not because we don't have a standard. Confusion is possible.

The only confusion I can see is if you intended for the 4 to be an exponent of the 3 and didn't know how to do that inline, or if you did actually intend for the 4 to be a separate numeral in the same term? And I'm confused because you haven't used inline notation in a place that doesn't support exponents of exponents without using inline notation (or a screenshot of it).

As written, which inline would be written as (2^3)4, then it's 32. If you intended for the 4 to be an exponent, which would be written inline as 2^3^4, then it's 2^81 (which is equal to whatever that is equal to - my calculator batteries are nearly dead).

We do have a standard, and I told you what it was. The only confusion here is whether you didn't know how to write that inline or not.

Try reading the whole sentence. There is a standard, I'm not claiming there isn't. Confusion exists because operating against the standard doesn't immediately break everything like ignoring brackets would.

Just to make sure we're on the same page (because different clients render text differently, more ambiguous standards...), what does this text say?

It should say

2^3^4; "Two to the power of three to the power of four". The proper answer is 2⁸¹, but many math interpreters (including Excel, MATLAB, and many students) will instead compute 8⁴, which is quite different.We have a standard because it's ambiguous. If there was only one way to do it, we'd just do that, no standard needed. You'd need to go pretty deep into kettle math or group theory to find atypical addition for example.

Ah ok. Sorry, got caught out by a double negative in your sentence.

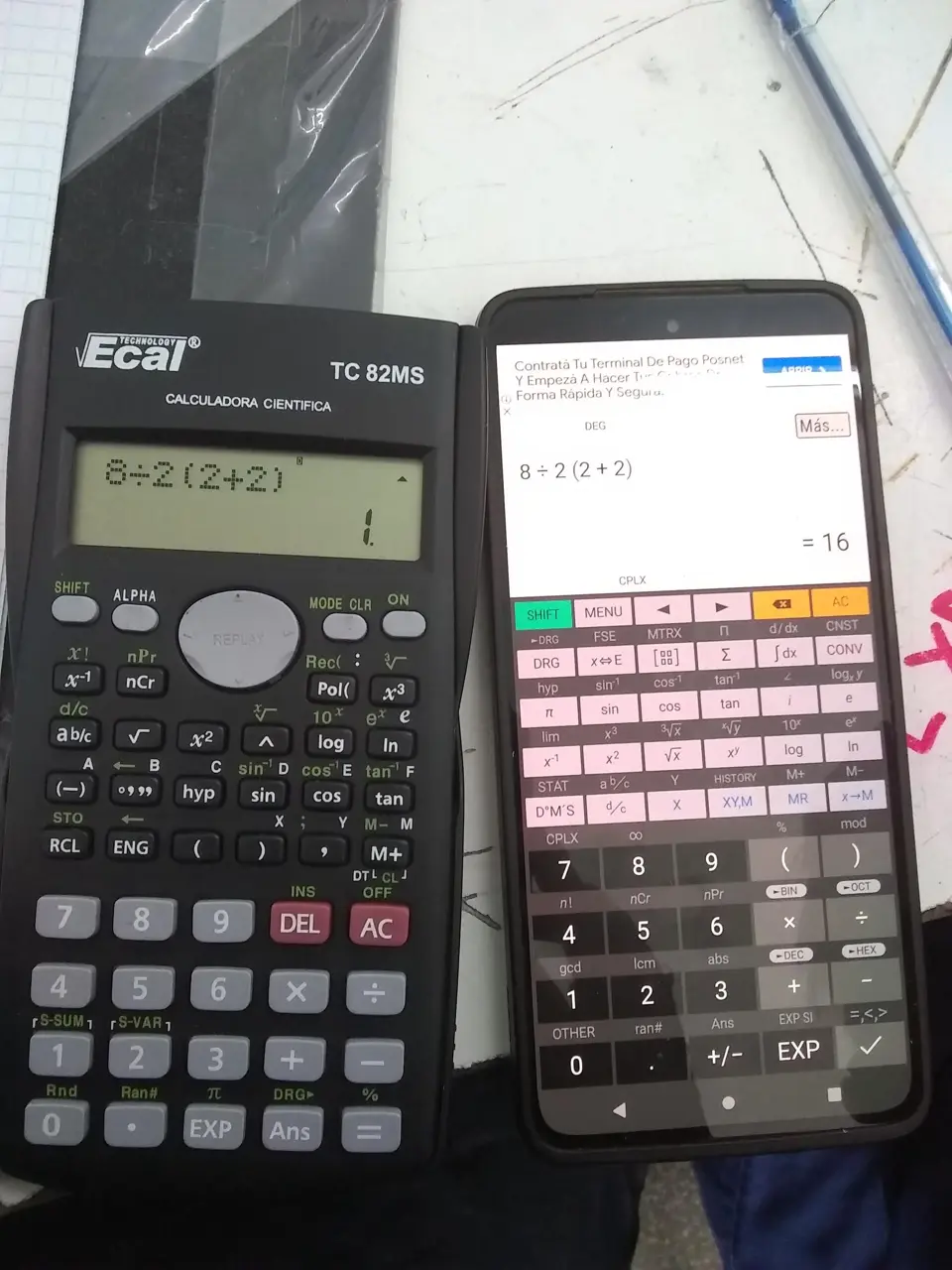

Ah but that's exactly the original issue in this thread - the e-calc is ignoring the rules pertaining to brackets. i.e. The Distributive Law.

Ah ok. Well that was my only confusion was what you had actually intended to write, not how to interpret it (depending on what you had intended). Yes should be interpreted 2^81.

Yeah, but Excel won't let you put in a factorised term either. It's just severely broken because the people who wrote it didn't bother checking the rules of Maths first. Programmers not knowing the rules of Maths doesn't mean Maths is ambiguous (it certainly creates a lot of confusion though!).

Disagree. There is one way to do it - follow the rules of Maths. That's why they exist. The order of operations rules are at least 400 years old, and make it not ambiguous. If people aren't obeying the rules then they're just wrong - that doesn't make it ambiguous. It's like saying if e-calcs started saying 1+1=3 then that must mean 1+1 is ambiguous. It might create confusion, but it doesn't mean the Maths is ambiguous.

This is exactly right. It's not a law of maths in the way that 1+1=2 is a law. It's a convention of notation.

The vast majority of the time, mathematicians use implicit multiplication (aka multiplication indicated by juxtaposition) at a higher priority than division. This makes sense when you consider something like 1/2x. It's an extremely common thing to want to write, and it would be a pain in the arse to have to write brackets there every single time. So 1/2x is universally interpreted as 1/(2x), and not (1/2)x, which would be x/2.

The same logic is what's used here when people arrive at an answer of 1.

If you were to survey a bunch of mathematicians—and I mean people doing academic research in maths, not primary school teachers—you would find the vast majority of them would get to 1. However, you would first have to give a way to do that survey such that they don't realise the reason they're being surveyed, because if they realise it's over a question like this they'll probably end up saying "it's deliberately ambiguous in an attempt to start arguments".

Yes it is, literally! The Distributive Law, and Terms. Also 1+1=2 isn't a Law, but a definition.

Correct, Terms - ab=(axb).

Don't ask either - this is actually taught in Year 7.

The university people, who've forgotten the rules of Maths, certainly say that, but I doubt Primary School teachers would say that - they teach the first stage of order of operations, without coefficients, then high school teachers teach how to do brackets with coefficients (The Distributive Law).

Sorry but both my phone calculator and TI-84 calculate 1/2X to be the same thing as X/2. It's simply evaluating the equation left to right since multiplication and division have equal priorities.

X = 5

Y = 1/2X => (1/2) * X => X/2

Y = 2.5

If you want to see Y = 0.1 you must explicitly add parentheses around the 2X.

Before this thread I have never heard of implicit operations having higher priority than explicit operations, which honestly sounds like 100% bogus anyway.

You are saying that an implied operation has higher priority than one which I am defining as part of the equation with an operator? Bogus. I don't buy it. Seriously when was this decided?

I am no mathematics expert, but I have taken up to calc 2 and differential equations and never heard this "rule" before.

...and they're both wrong, because they are disobeying the order of operations rules. Almost all e-calculators are wrong, whereas almost all physical calculators do it correctly (the notable exception being Texas Instruments).

The rules of Terms and The Distributive Law, somewhere between 100-400 years ago, as per Maths textbooks of any age. Operators separate terms.

I'm a High School Maths teacher/tutor, and have taught it many times.

I can say that this is a common thing in engineering. Pretty much everyone I know would treat 1/2x as 1/(2x).

Which does make it a pain when punched into calculators to remember the way we write it is not necessarily the right way to enter it. So when put into matlab or calculators or what have you the number of brackets can become ridiculous.

I'm an engineer. Writing by hand I would always use a fraction. If I had to write this in an email or something (quickly and informally) either the context would have to be there for someone to know which one I meant or I would use brackets. I certainly wouldn't just wrote 1/2x and expect you to know which one I meant with no additional context or brackets

By the definition of Terms, ab=(axb), so you most certainly can write that (and Maths textbooks do write that).

The real answer is that anyone who deals with math a lot would never write it this way, but use fractions instead

Yes, they would - it's the standard way to write a factorised term.

Fractions and division aren't the same thing.

Are you for real? A fraction is a shorthand for division with stronger (and therefore less ambiguous) order of operations

Yes, I'm a Maths teacher.

I added emphasis to where you nearly had it.

½ is a single term. 1÷2 is 2 terms. Terms are separated by operators (division in this case) and joined by grouping symbols (fraction bars, brackets).

1÷½=2

1÷1÷2=½ (must be done left to right)

Thus 1÷2 and ½ aren't the same thing (they are equal in simple cases, but not the same thing), but ½ and (1÷2) are the same thing.

So are you suggesting that Richard Feynman didn't "deal with maths a lot", then? Because there definitely exist examples where he worked within the limitations of the medium he was writing in (namely: writing in places where using bar fractions was not an option) and used juxtaposition for multiplication bound more tightly than division.

Here's another example, from an advanced mathematics textbook:

Both show the use of juxtaposition taking precedence over division.

I should note that these screenshots are both taken from this video where you can see them with greater context and discussion on the subject.

It's called Terms - Terms are separated by operators and joined by grouping symbols. i.e. ab=(axb).

Mind you, Feynmann clearly states this is a fraction, and denotes it with "/" likely to make sure you treat it as a fraction.

It's not the slash which makes it a fraction - in fact that is interpreted as division - but the fact that there is no space between the 2 and the square root - that makes it a single term (therefore we are dividing by the whole term). Terms are separated by operators (2 and the square root NOT separated by anything) and joined by grouping symbols (brackets, fraction bars).

Yep with pen and paper you always write fractions as actual fractions to not confuse yourself, never a division in sight, while with papers you have a page limit to observe. Length of the bars disambiguates precedence which is important because division is not associative; a/(b/c) /= (a/b)/c. "calculate from left to right" type of rules are awkward because they prevent you from arranging stuff freely for readability. None of what he writes there has more than one division in it, chances are that if you see two divisions anywhere in his work he's using fractional notation.

Multiplication by juxtaposition not binding tightest is something I have only ever heard from Americans citing strange abbreviations as if they were mathematical laws. We were never taught any such procedural stuff in school: If you understand the underlying laws you know what you can do with an expression and what not, it's the difference between teaching calculation and teaching algebra.

There is, especially if you're dividing by a fraction! Division and fractions aren't the same thing.

Not if it actually is a division and not a fraction. There's no problem with having multiple divisions in a single expression.

Semantically, yes they are. Syntactically they're different.

No, they're not. Terms are separated by operators (division) and joined by grouping operators (fraction bar).

That's syntax.

...let me take this seriously for a second.

The claim "Division and fractions are semantically distinct" implies that they are provably distinct functions, we can use the usual set-theoretic definition of those. Distinctness of functions implies the presence of pair

n, m, elements of an appropriate set, say, the natural numbers without zero for convenience, such that (excuse my Haskell)div n m /= fract n m, where/=is the appropriate inequality of the result set (the rational numbers, in this example, which happens to be decidable which is also convenient).Can you give me such a pair of numbers? We can start to enumerate the problem. Does

div 1 1 /= fract 1 1hold? No, the results are equal, both are1. How aboutdiv 1 2 /= fract 1 2? Neither, the results are both the same rational number. I leave exploring the rest of the possibilities as an exercise and apologise for the smugness.You need to take it seriously for longer than that.

No, I'm explicitly stating they are.

This is literally Year 7 Maths - I don't know why some people want to resort to set theory.

But that's the problem with your example - you only tried it with 2 numbers. Now throw in another division, like in that other Year 7 topic, dividing by fractions.

1÷1÷2=½ (must be done left to right)

1÷½=2

In other words 1÷½=1÷(1÷2) but not 1÷1÷2. i.e. ½=(1÷2) not 1÷2. Terms are separated by operators (division in this case) and joined by grouping symbols (brackets, fraction bar), and you can't remove brackets unless there is only 1 term left inside, so if you have (1÷2), you can't remove the brackets yet if there's still some of the expression it's in left to be solved (or if it's the last set of brackets left to be solved, then you could change it to ½, because ½=(1÷2)).

Therefore, as I said, division and fractions aren't the same thing.

Apology accepted.

I'm not asking you to explain how division isn't associative, I'm asking you to find an n, m such that ⁿ⁄ₘ is not equal to n ÷ m.

To compare two functions you have to compare them one to one, you have to compare ⁄ to ÷, not two invocation of one to three invocation of the others or whatever.

Also I'll leave you with this. Stop being confidently incorrect, it's a bad habit.

EDIT: OMG you're on programming.dev. A programmer should understand the difference between syntax and semantics. This vs. this. Mathematicians tend to call syntax "notation" but it's the same difference.

Another approach: If

fracanddivare different functions, then multiplication would have two different inverses. How could that be?The opposite of div is to multiply. The opposite of frac is to invert the fraction.

I was explaining why we have the rule of Terms (which you've not managed to find a problem with).

I already pointed out that's irrelevant - it doesn't involve a division followed by a factorised term. You're asking me to defend something which I never even said, nor is relevant to the problem. i.e. a strawman designed to deflect.

You haven't shown that anything I've said is incorrect. If you wanna get back on topic, then come back to showing how 1÷½=1÷(1÷2) but not 1÷1÷2 is, according to you, incorrect (given you claimed division and fractions are the same thing)

Yeah, welcome to why I'm trying to get programmers to learn the rules of Maths

I said:

You replied:

Thus, you made a claim about semantics. One which I then went on and challenged you to prove, which you tried to do with a statement about syntax.

I did not say "opposite". I said "inverse". That term has a rather precise meaning.

Your statement there is correct. It is also a statement about syntax, not semantics. Divisions and fractions are distinct in syntax, but they still both are the same functions, they both are the inverse of multiplication.

PEMDAS is not a rule of maths. It's a bunch of bad American maths pedagogy. Is, in your opinion, "show your work" a rule of maths? Or is it pedagogy?

And told you what it was.

Which I did with a concrete example, which you have since ignored.

The inverse of div is to multiply. The inverse of frac is to invert the fraction - happy now?

No, they're not. Division is a binary operator, a fraction is a single term.

Multiplication is also a binary operator, and division is the opposite of it (in the same way that plus and minus are unary operators which are the opposite of each other). A fraction isn't an operator at all - it's a single term. There is no "opposite" to a single term (except maybe another single term which is the opposite of it. e.g. the inverse fraction).

No, it's a mnemonic to remind people of the actual rules.

You have given nothing of that sort. You provided a statement about a completely orthogonal topic instead. "Prove that the sky is blue" -- "Here, grass is green" -- "That doesn't answer the question" -- "Nu-uh it does!". That's you. That "Nu-uh".

"Inverting a fraction" is not a functional inverse. You're getting led astray by terminology, those two uses of the word "invert" have nothing to do with each other, it's a case of English having bad terminology (in German we use different terms so the confusion doesn't even begin to apply).

Go read that wikipedia article I linked. Can you even read it. Do you have the necessary mathematical literacy.

Do you want to tell me that fractions don't take two numbers? That two numbers applied to division don't form a term?

Inverse. I read elsewhere that you're a math teacher and this is just such a perfect example of what's wrong with math ed: Teachers don't even know the fucking terminology. You don't know maths. You know a couple of procedural rules you shove into kids, rules that have to be un-taught in university because nothing of it has anything to do with actual maths.

There's no such thing anywhere but in the US. Those rules are a figment of the imagination of the US education system.

You are up to your scalp in the Dunning-Kruger effect. Two possibilities: You quadruple down and become increasingly bitter, or you find yourself an authority that you trust, e.g. a university professor, and ask them in person. Ask a Fields Medalist if you can get hold of one. You think you know more about this than me. Motherfucker you do not, but I also acknowledge that I'm just some random guy on the internet to you.

If you want to continue this, I have one condition: Explain, in your own words, the difference between syntax and semantics. If you have done that, done that homework, I'm willing to resume your education. Otherwise, take the given advice and get lost I've got better things to do than to argue with puerile windbags.

Now you're getting it! Correct, they don't. They form an expression. Terms are separated by operators, and joined by grouping symbols. Expressions are made up of terms and operators (since, you know, operators separate terms). I told you way back in the beginning that 1÷2 is 2 terms, and ½ is 1 term. Getting back to the original question, 2(2+2) is 1 term and 2x(2+2) is 2 terms.

Which time that I mentioned textbooks, historical Maths documents, and proofs did you miss?

University professors don't teach order of operations - high school teachers do. That's like saying "Ask the English teacher about Maths".

Why would I want to when you ignore Maths textbooks and proofs? See my first comment in this post that you've finally got the difference now. See ya.

Terms, expressions, symbols, all those are terms about syntax. Not semantics. Do you start to notice something?

To learn. I challenge you again to explain the difference between syntax and semantics. Last chance.