Tyranny

Rules

- Don't do unto others what you don't want done unto you.

- No Porn, Gore, or NSFW content. Instant Ban.

- No Spamming, Trolling or Unsolicited Ads. Instant Ban.

- Stay on topic in a community. Please reach out to an admin to create a new community.

You might still think about Eric Schmidt as a “(big) tech guy” and businessman, but his passion for (geo)politics was always evident, even while he served as Google’s CEO.

These days, Schmidt is the chair of the Special Competitive Studies Project (SCSP), a think tank that would like to position itself as a reference point to a military alliance, NATO, and get it to “monitor disinformation in real-time.”

SCSP’s ambition is no less than to help craft new national security strategies, always with an eye on the alleged attempts to increase disinformation (here AI is to blame) – but also ways to combat that, and here, SCSP says (the US) must strengthen its “AI competitiveness.”

The goal is to “win” what’s referred to as the techno-economic competition by 2030 – there’s that deadline, favored by many a controversial globalist initiative.

Here, the group would like NATO and its members to fight against what is described as AI disinformation, that new chapter in information warfare.

Schmidt’s think tank doesn’t like what’s seen as the current reactive approach and the tired old debunking. That means there must be an “active” one – and the replacement for debunking would logically be some form of the dystopian concept of “prebunking.”

(SCSP mentions both as desirable methods in a late 2022 report, but this time shies away from using the latter term.)

SCSP wants various actors to carry out real-time surveillance of “disinformation” by means of spending money on tools fed with publicly available online data (aka, the cynically named “open source” data).

In other words, real-time mass-scale internet data scraping. Such tools already exist and are used by law enforcement, causing various levels of controversy.

Next comes prebunking, even if the latest batch of SCSP recommendations stops short of calling it that.

But what would you call it?

“NATO should provide its own positive narrative to get out ahead of disinformation, and highlight failures of authoritarian regimes, especially on their own digital platforms.”

And to make this work, SCSP wants NATO to co-opt various governments and companies, as well as NGOs. Inside the alliance, a “disinformation unit” should be formed.

Last but not least, the think tank says – “Foster healthy skepticism.”

Perhaps starting with SCSP’s own roles, goals, and affiliations.

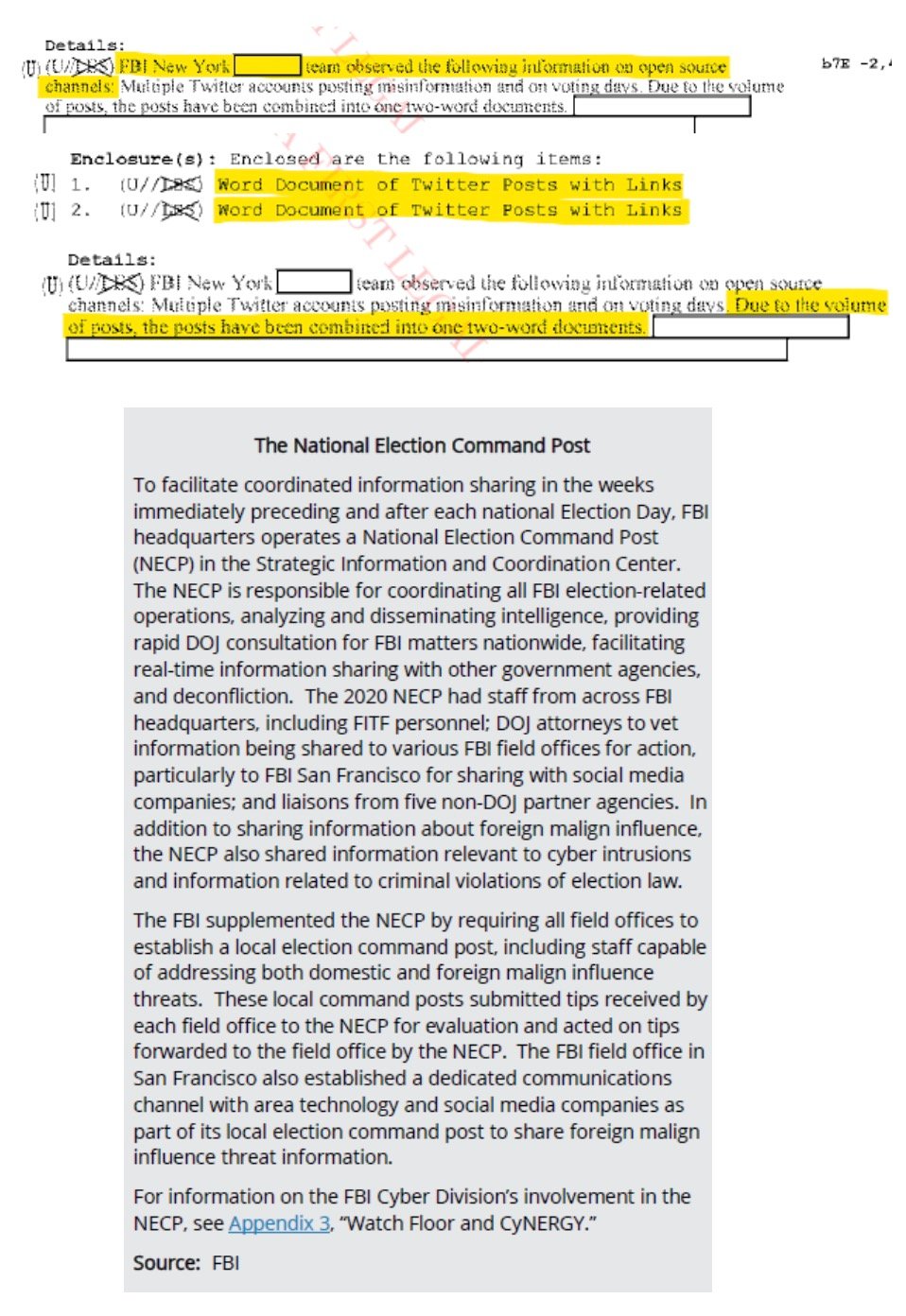

America First Legal (AFL) has disclosed documents obtained through a lawsuit against the FBI and the Department of Justice (DOJ), accusing them of concealing federal records that detail government-sponsored censorship by the Biden-Harris administration before the 2022 midterm elections.

The documents revealed that the FBI’s National Election Command Post (NECP) had compiled lists of social media accounts posting what they considered “misinformation,” extending from New York to San Francisco. This included the Right Side Broadcasting Network, cited by Matt Taibbi as targeted for “additional action” by the FBI.

These lists were so extensive that they were compiled into Word documents “due to the volume of posts.” NECP, operating from the FBI Headquarters and aided by DOJ attorneys and liaisons from five non-DOJ agencies, was responsible for vetting the information and directing actions across various field offices. They focused not only on foreign threats but also on cyber intrusions and potential criminal violations linked to election law.

Domestically, accounts like “@RSBNetwork” were flagged for issues related to election law violations, seemingly unconnected to foreign influence or cyber threats. NECP specifically instructed the San Francisco field office to send “preservation letters” to maintain relevant user information until legal actions could be formally initiated.

The Inspector General’s report outlines the legal procedures the FBI might use to compel evidence production from third parties. These range from grand jury subpoenas for current subscriber information, including personal details and payment methods, to district court orders for historical data under the Electronic Communications Privacy Act. In more severe cases, the FBI might request a search warrant for detailed content or ongoing investigation data.

This pattern of surveillance and legal pressure reflects a broader governmental approach that views alleged “misinformation” as a law enforcement issue. This stance has led to significant concerns about free speech, especially given recent cases where individuals faced prosecution for online activities deemed misleading by authorities.

Elon Musk has suggested that the European Union attempted to coerce him with an underhanded deal to secretly implement censorship within his platform. Musk further added that EU-designed negotiations were accepted by other online platforms. However, he outrightly rejected the concealed deal.

On Friday, the EU made strides in evidencing the potency of its fresh Digital Services Act (DSA) by launching an attack on X, which is owned by Musk.

The group accused X of being in violation of specific EU regulations and threatened the platform with punitive fines. In response to this, Musk was quick to counter-attack by criticizing the DSA as a “canned misinformation” source. He further revealed that the EU had solicited a clandestine deal with him for entering into censorship pertaining to the EU’s directives.

In his revelation, Musk stated, “The European Commission offered [X] an illegal secret deal: if we quietly censored speech without telling anyone, they would not fine us.” He assured his stance by saying, “The other platforms accepted that deal,” however, he did not agree to participate. He also expressed his anticipations for the future, saying, “We look forward to a very public battle in court, so that the people of Europe can know the truth.”

The European Union criticized X for its lack of transparency and pointed out that social media platforms are obligated to counteract “illegal content” as well as “risks to public security” as per its regulations. Furthermore, the EU claimed that it was discontent with the X’s blue check system, deeming it incompatible with the “industry practice.”

In case of non-compliance with EU’s stipulations, X could face repercussions, including a potential fine equivalent to six percent of its total global turnover.

The Japanese chair of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has come out with a report calling for the US and Japan to team up on “combating disinformation.”

Christopher B. Johnstone also wants the two countries to engage in several censorship techniques, such as removing content (“false narratives” – regular censorship) but also a considerably more dystopian one known as “prebunking.”

That would be, suppressing narratives by revealing them as “misinformation” before they become public, thus eroding the very perception of their trustworthiness, while equating this as introducing “mental antibodies” into a population, and other outlandish language has been used in the past to justify the tactic.

CSIS mentions in a press release announcing the report that Johnstone had a meeting with Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs Director of Public Diplomacy Strategy Division Hideaki Ishii, “to discuss how the United States and Japan can cooperate to address this critical challenge” (namely, combating “disinformation”).

Not for nothing – CSIS is not your run-of-the-mill nonprofit, and access to government structures in other countries is not surprising, given its origins and image as one of those think tanks that have an oversized influence on US foreign policy.

Now, CSIS wants Japan and the US to tackle “information operations” such as (real or labeled as such) disinformation threats. The report seeks to establish an agenda to increase this collaboration and mentions that the paper includes “the results of a closed-door conference held at CSIS in February” – attended by “experts” from both countries.

The part of the report that addresses strategies to counter the threat, defined by CSIS, includes public education and media literacy, AI (as a tool of censorship – but without failing to mention the same tech as supposedly a grave threat to democracies when it’s used to create deepfakes).

Another thing CSIS likes is “fact-checking” (while critical of Japan as being “somewhat late” to this particular game), as well as debunking.

And then, there’s “prebunking” which CSIS chooses to describe as a method that proactively issues “forewarnings” and also “preemptively refutes false narratives.”

Coming back to Earth a little bit, so to speak – in terms of championing more conventional information control tools, the CSIS strategy lastly mentions “labeling, transparency, and risk monitoring.”

Canada’s government has decided to spend some $146.6 million (CAD 200 million) and employ, full-time, 330 more people to be able to implement the Online Harms Act (Bill C-63).

That is the monetary cost of bureaucratic red tape necessary to make this bill, which has moved for a second reading in Canada’s House of Commons, eventually happen.

At the same time, the cost to the country’s democracy could be immeasurable – given some of this sweeping censorship legislation’s more draconian provisions, primarily focused on what the authorities choose to consider to be “hate speech.”

Some of those provisions could land people under house arrest, and have their internet access cut simply for “fear” they could, going forward, commit “hate crime” or “hate propaganda.”

If these are found to be committed in conjunction with other crimes, the envisaged punishment could be life in prison. Meanwhile, money fines go up to $51,080. And, to make matters even more controversial, the proposed law appears to apply to statements retroactively, namely, those made before Bill C-63’s possible passage and enactment as law.

The new body, the Digital Safety Commission, Ombudsperson, and Office will be in charge, and this is where the money will go and where the staff amount to 330 people. The spending estimate that has recently come to light covers the five years until 2029.

The office’s task – if the bill passes – will be to monitor, regulate, and censor online platforms, as per the Online Harms Act. Critics of the law are making a point of the distorted sense of priorities among Canada’s currently ruling regime, where a large amount of money is to be spent here, while vital sectors – such as combating actual, real-life serious crimes face funding restrictions.

Some of the purely pragmatic opposition to the bill has to do with the belief that it will – while violating citizens’ freedoms and rights – actually, prove to be unable to tackle what it is supposedly designed to do – various forms of online harassment.

And that’s not all. “Canadian taxpayers will likely be stuck footing the bill for a massive bureaucracy that will allow Big Tech companies to negotiate favorable terms with non-elected regulators behind closed doors,” is how MP Michelle Rempel Garner articulated it.

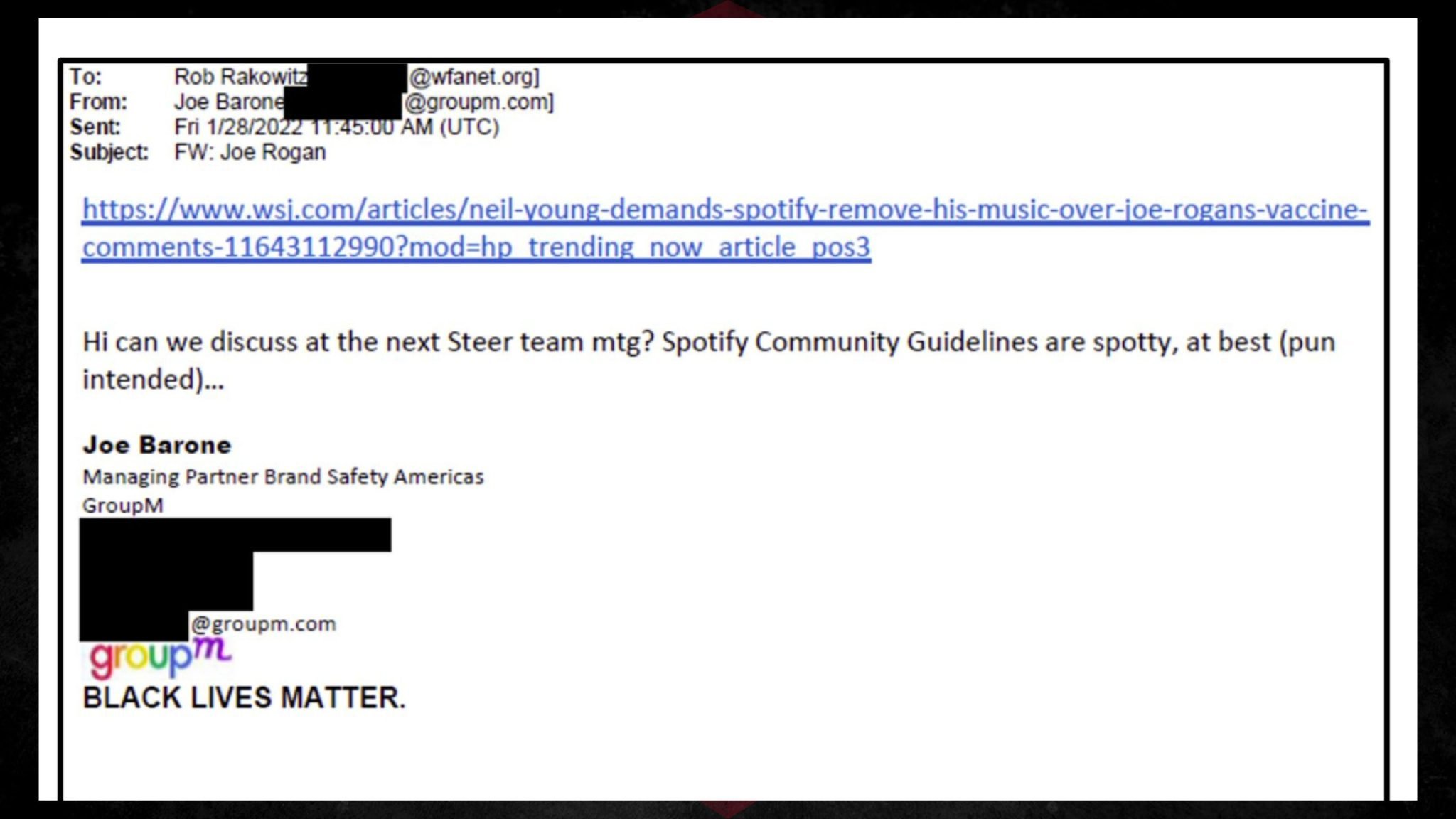

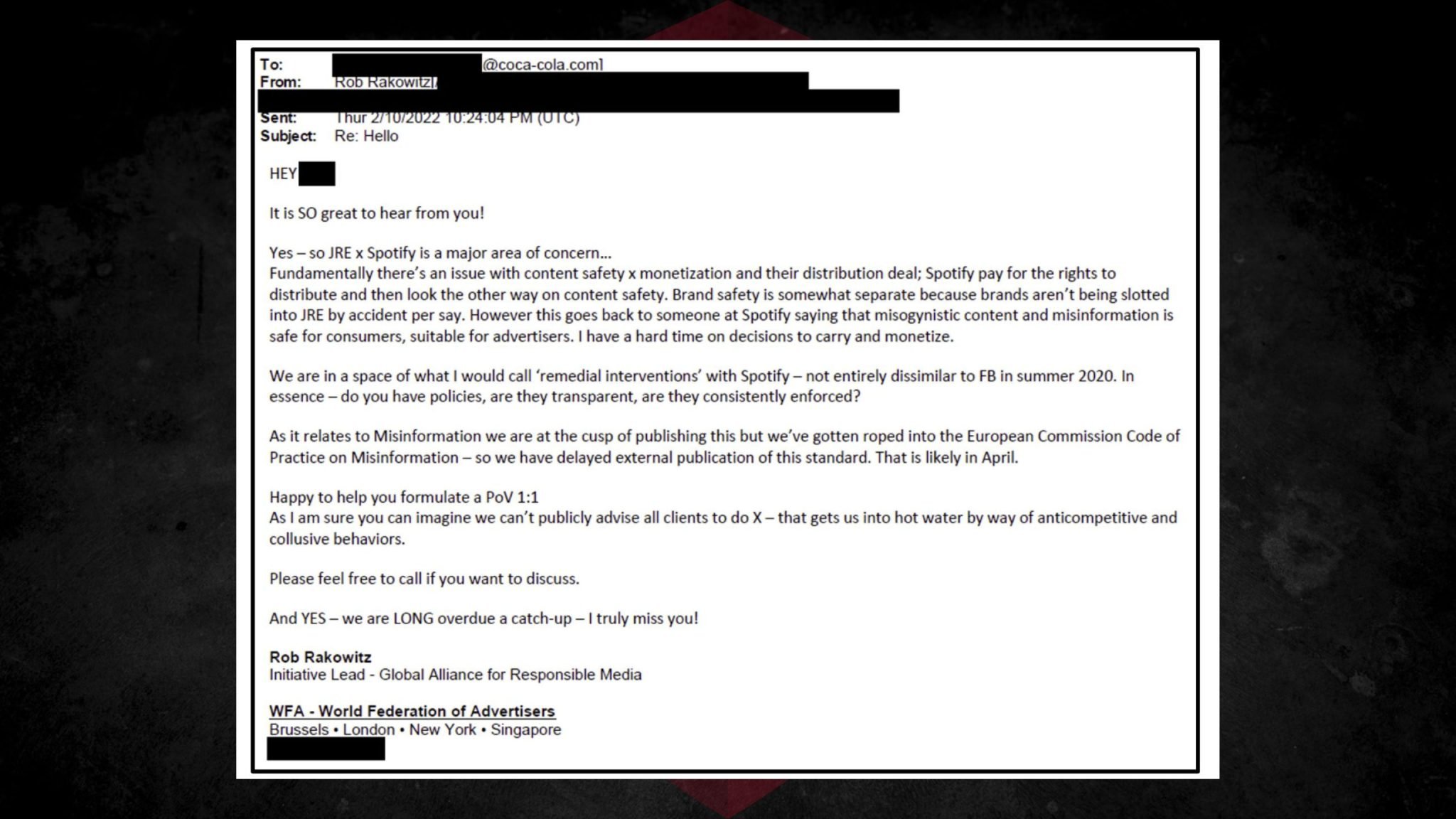

A new report from the House Judiciary Committee released on Wednesday, and confirming our previous reporting, casts the Global Alliance for Responsible Media (GARM) under scrutiny, suggesting potential violations of federal antitrust laws due to its outsized influence in the advertising sector.

We obtained a copy of the report for you here.

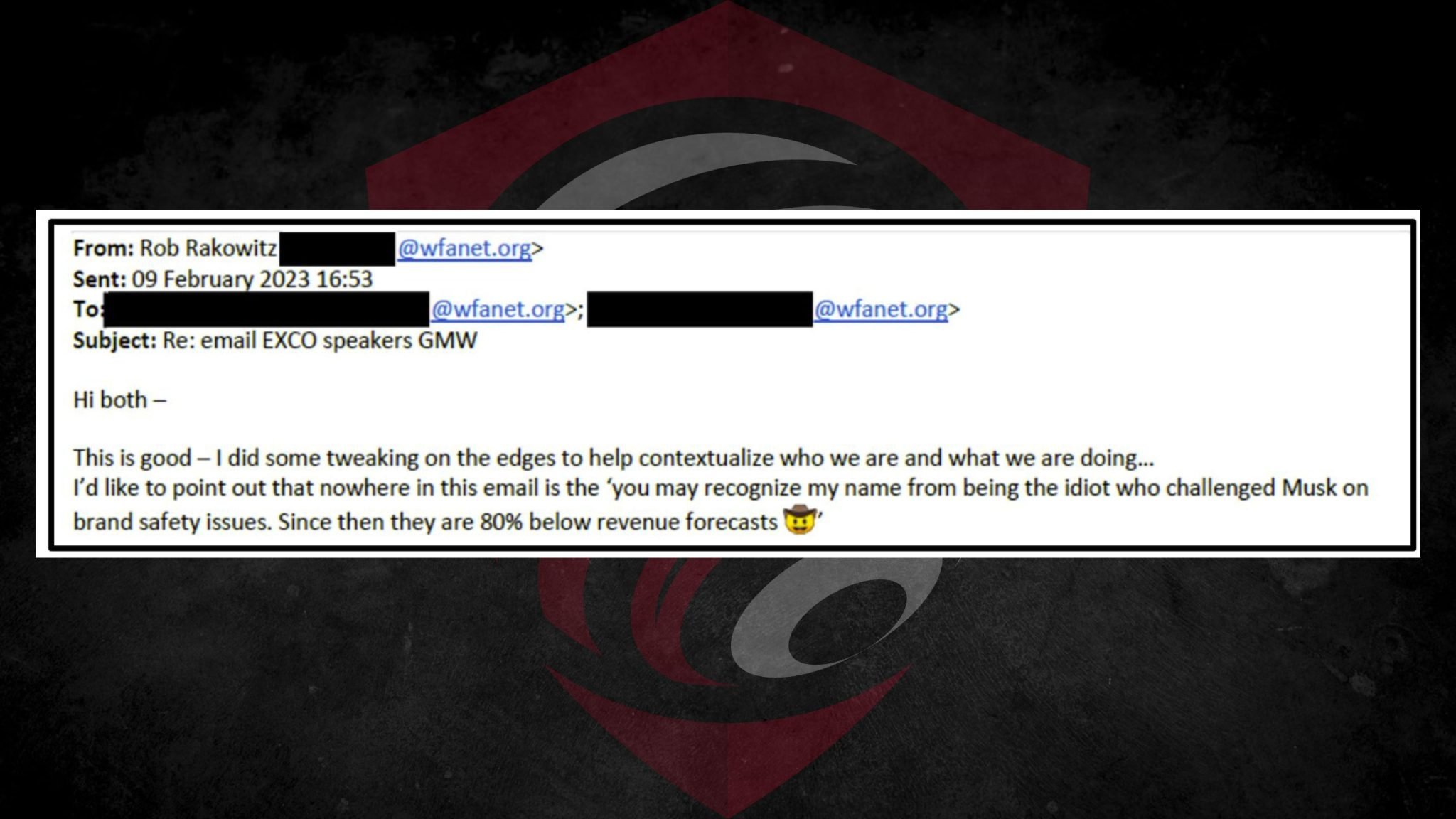

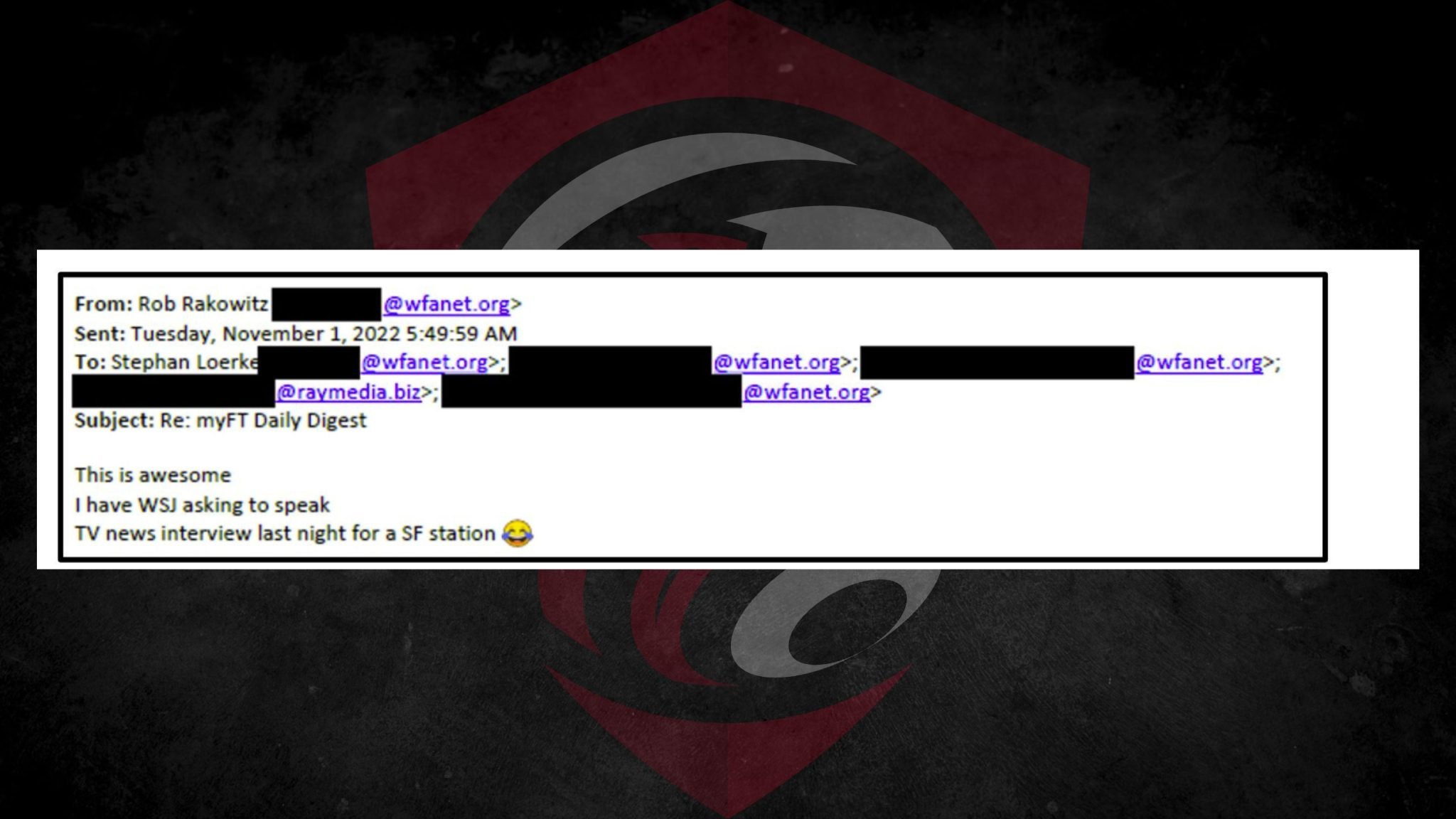

Established in 2019 by Rob Rakowitz and the World Federation of Advertisers, GARM has been accused of leveraging this influence to systematically restrict certain viewpoints online and sideline platforms advocating divergent views.

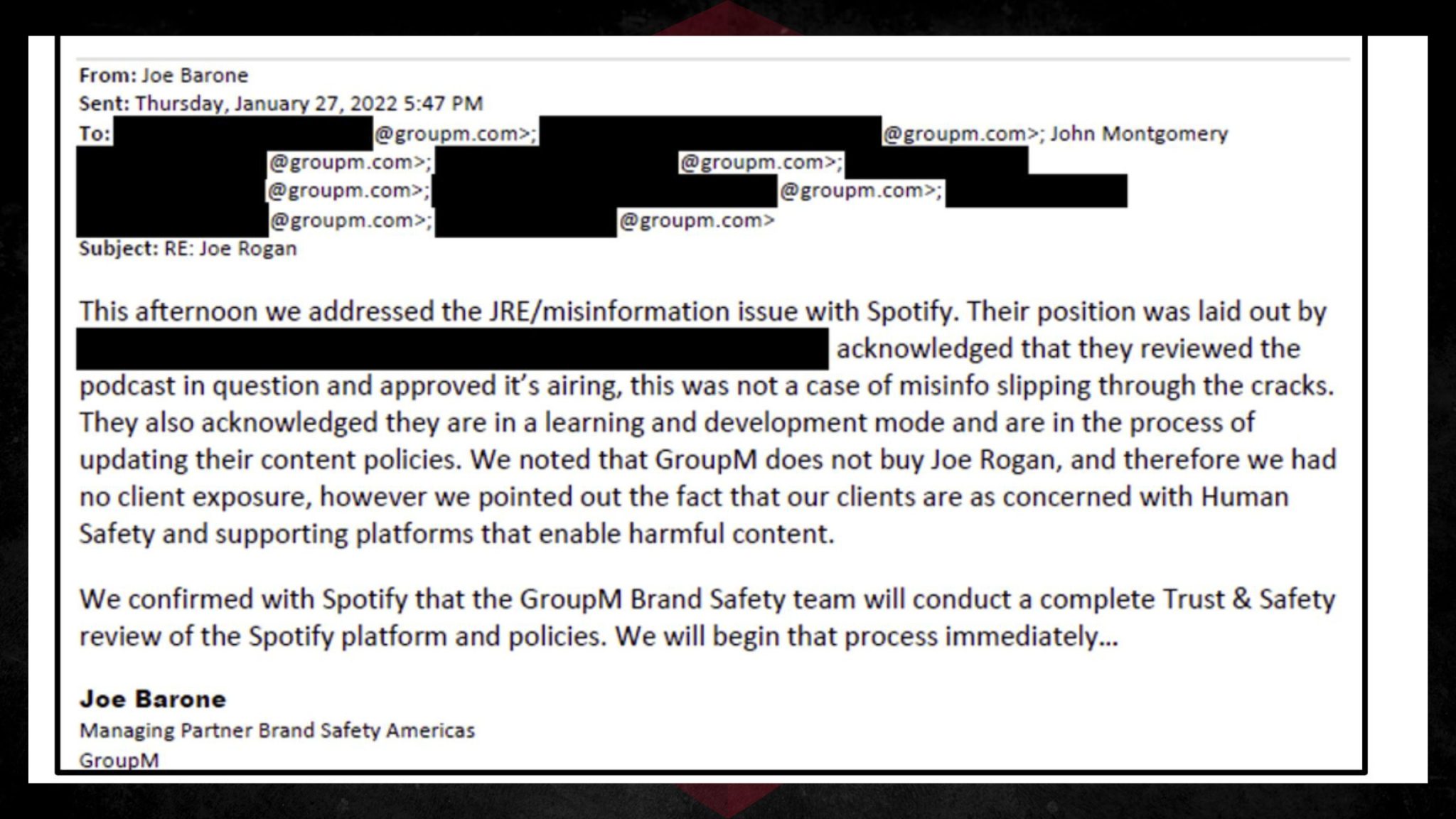

The organization, initially conceived to manage the surge of free speech online, is reported to coordinate with major industry players including Proctor & Gamble, Mars, Unilever, Diageo, GroupM, and others. The collaboration appears to stretch across the largest ad agency holding companies worldwide, known collectively as the Big Six. Such collaboration raises concerns about a concerted effort to police content, especially content that challenges mainstream narratives.

Specifically, the report highlights GARM’s actions following the rebranding of Twitter by Elon Musk and its attempts to silence discussions on controversial topics like COVID-19 vaccines on Spotify’s “The Joe Rogan Experience.” Despite no “brand safety” risks acknowledged by GroupM, GARM still pressed for advertising restrictions on Rogan’s podcast.

Moreover, internal communications within GARM reveal selective targeting against platforms like The Daily Wire, categorized under the “Global High Risk exclusion list” for purportedly promoting “Conspiracy Theories.” The report also includes examples where GARM leaders expressed disdain towards conservative outlets such as Fox News, The Daily Wire, and Breitbart News, aiming to curtail their advertising revenue by labeling their content as objectionable.

The committee’s findings suggest that GARM’s methods not only potentially contravene Section 1 of the Sherman Act, which prohibits conspiracies that restrain commerce but also infringe upon fundamental American freedoms by censoring protected speech. This has raised significant concerns about the implications for democratic values and the diversity of voices in the American public sphere.

In response to these allegations, the House Judiciary Committee has called for a hearing, which was held today, to examine whether the current antitrust law enforcement and penalties are sufficient to address such collusive behaviors within online advertising, signaling a critical review of how advertising power is wielded in the digital age.

Another week, another controversy involving the conduct of Australia’s eSafety Commissioner Julie Inman Grant.

Grant’s job officially is to direct efforts against misinformation and other online harms – but her actions have earned her the pejorative “titles” of the country’s “chief censor” and “censorship czar.”

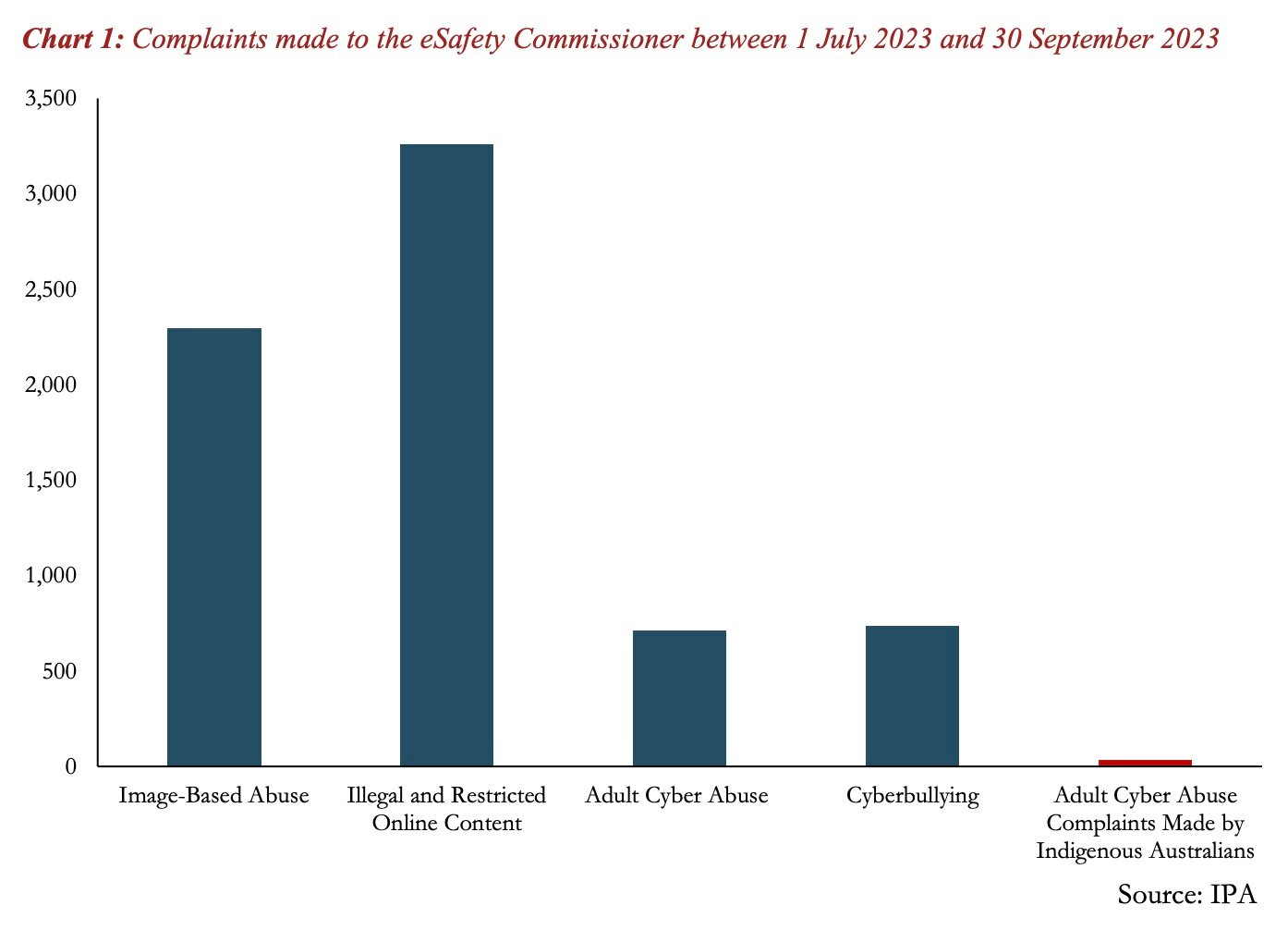

The latest round of criticism aimed Grant’s way has to do with her role around last year’s failed Indigenous Voice referendum, when, according to newly unearthed documents (the result of the Institute of Public Affairs, IPA, FOIA requests) this official in fact contributed to spreading misinformation, rather than combating it – and making the dreaded “divisive debates” even worse.

It appears Grant’s tactic to shore up the policy pushed by the “yes” camp ahead of the referendum was to make unfounded claims about the number of race-related complaints her office was likely to receive from Indigenous Australians, as well as the number of racially motivated online incidents.

As the referendum, held in mid-October 2023, was approaching, Grant spoke for the Australian to, effectively, engage in fearmongering around the issue, when she said she expected this type of attack to rise ahead of the vote.

Grant also claimed at the time that levels of online abuse targeting this part of the population were already “high.”

However, the FOIA documents suggest that she was exaggerating the threat for political (and possibly funding) reasons. It has now been revealed that from January 2022 until October 2023, Grant’s office received a total of two complaints from Indigenous Australians that specifically had to do with the upcoming referendum.

As it was approaching – from July to September last year – this number was 30 – or 0.4% percent of all complaints eSafety had received. And not in a single case related to the referendum did this content eventually warrant removal.

All this begs the question of Grant’s intent while coming up with “dire warnings” apparently unsupported by any facts available to her.

One result was that the government increased her agency’s budget to $42.5 million per year (from $10.3). And then there was simply “politically charged censorship,” as IPA Director of Law and Policy John Storey described it.

Storey added: “The narrative Julie Inman Grant has sought to establish, that there was a wave of racist cyber abuse during the referendum, is not supported by her own office’s data.”

Barbara McQuade, who was in 2017 dismissed from her job as US Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan, has in the meantime turned into quite something of a “misinformation warrior.”

Earlier this year McQuade – who in the past also worked as co-chair of the Terrorism and National Security Subcommittee of the Attorney General’s Advisory Committee in the Obama Administration – published a book, “Attack from Within: How Disinformation is Sabotaging America.”

Now, she herself is attacking the First Amendment as standing in the way of censorship (“content moderation”) and advocating in favor of essentially finding ways to bypass it. Opponents might see this as particularly disheartening, coming from somebody who used to hold such a high judicial office.

“The better course for regulating social media and online content might be to look at processes versus content because content is so tricky in terms of First Amendment protections. Regulating some of the processes could include things like the algorithms,” McQuade said.

This point – that the First Amendment serves precisely the purpose it was designed for – has lately been cropping up more and more frequently in the liberal spectrum of US politics, with the situation resembling a coordinated “narrative building.”

McQuade also sticks to the script, as it were, on other common talking points this campaign season: the dangers of AI (as a tool of “misinformation” – but the same camp loves AI as a tool of censorship). In the scenario where AI is perceived as a threat, McQuade wants new laws to regulate the field.

And she repeats the suddenly renewed calls to change CDA’s Section 230 in a particular way – namely, a way that pressures social platforms to toe the line, or else see legal protections afforded to them eroded.

This is phrased as amending the legislation to provide for civil liability, i.e., “money damages” if companies behind these platforms are found to not force users to label AI-generated content or delete bot accounts diligently enough.

McQuade’s comments regarding Section 230 are made in the context of her ideas on “regulating processes rather than content” (as a way to circumvent the First Amendment).

While on the face of it, stepping up bot removal sounds reasonable, there are reasons to fear this could be yet another false narrative whose actual goal is punishing platforms for not deleting real accounts falsely accused of being “bots” by certain media and politicians.

The Hamilton 68 case, exposed in the Twitter Files, is an example of this.

Even the New York Times looks like it’s treading somewhat lightly while publishing articles aimed at dismantling the very concept of the First Amendment.

An opinion piece penned by an Obama and Biden administration adviser, Tim Wu, is therefore labeled as a “guest essay.” But was it the author, or the newspaper, who decided on the title? Because it is quite scandalous.

“The First Amendment is Out of Control” – that’s the title.

Meanwhile, many believe that attacks on this speech-protecting constitutional amendment are what’s actually out of control these days.

Wu takes a somewhat innovative route to argue against free speech: he painstakingly frames it as concern that the universally mistrusted Big Tech might be abusing it, with the latest Supreme Court ruling regarding Texas and Florida laws, (ab)used as an example.

When the government colludes with mighty entities like major social platforms – the First Amendment becomes the primary recourse to defend speech now expressed in public square forums forged through the pervasiveness of the internet.

So despite Wu’s effort to make his message seem unbiased, the actual takeaways are astonishing: one is that the First Amendment is an obstacle for the government to protect citizens (for being invoked as a tool restraining censorship?)

But this means that the First Amendment, designed to protect citizens from government censorship, is doing its job.

In the same vein, contrary to the sentiment of this “essay,” the amendment is there not to protect “national security” – nor does free speech undermine that, in a democracy.

You don’t like TikTok? Let’s just ban it…but the pesky First Amendment stands in the way of that? What Wu ignores here is that the bill that allows banning TikTok is so ambiguous it can be used to get rid of other, for whatever reason, “disliked” apps.

Wu also doesn’t like that the amendment is used to counter privacy and security-undermining age verification laws, like California’s Age-Appropriate Design Code.

“Suicide pact” is how Wu referred to the impact of the First Amendment in the 1949 dissenting opinion in the Terminiello v. City of Chicago “riot incitement” case.

As has lately become the norm with the First Amendment detractors: this is lots of words, most of them empty, some dramatic, but overall, free speech-unfriendly.

The EU Council has managed to nestle fighting “disinformation and hate speech” between such issues as the Middle East, Ukraine, and migration – not to mention while at the same time appointing a new set of “apparatchiks,” in the wake of the European Parliament elections.

This proceeds from the Council’s 2024-2029 strategic agenda, adopted on June 27. This document represents a “five-year plan” to guide the bloc’s policy and goals.

Under the heading, “A free and democratic Europe,” the document addresses different ways in which “European values” will be upheld going forward. The Council’s conclusions state that in order to strengthen the EU’s “democratic resilience,” what it decides is disinformation and hate speech will have to be countered.

These categories of speech are infamously arbitrarily defined, even in legislation, and habitually used as a tool of censorship – but the conclusions count combating them among the strategic goal of fending off foreign interference and destabilization.

In other words, those individuals or organizations that are found to be “guilty” of hate speech or disinformation might face the grim possibility of being treated as, essentially, a threat to the EU’s security.

Another promise the document makes in the same breath is that tech giants will be made to “take their responsibility for safeguarding democratic dialogue online.”

Does this mean there will be more or less censorship in the EU over the next five years? The Brussels bureaucrats are at this point so practiced at churning out platitudes that, theoretically, this statement could be interpreted either way.

However, in conjunction with the “misinformation” etc., talk, it is fairly clear which course the EU intends to keep when it comes to online freedom of expression.

AI is not explicitly mentioned as a threat (either to the EU or by the EU, as the technology that can be used to ramp up censorship, aka, “combat misinformation”).

However, you name it, the EU supposedly has it: under the part of the conclusions addressing competitiveness, increasing capacities related to AI sits right there with growing defense, space, quantum technologies, semiconductors, health, biotechnologies capabilities – not to mention “net-zero technologies, mobility, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, and advanced materials.”

It’s a pretty comprehensive bridge the EU appears to be trying to sell to its member-states and their citizens.

Given how X has gone out of its way to reveal the depth and breadth of online censorship via the Twitter Files, this makes for an awkward reunion: the company has decided to rejoin the Global Alliance for Responsible Media (GARM).

It’s a pro-censorship, World Economic Forum-affiliated advertisers’ group, that achieves its objectives through the “brand safety” route (i.e., the censorship “brand” here would be demonetization). And last summer, it was scrutinized by the US Congress.

GARM is one of those outfits whose roots are very entangled (comes in handy when somebody tries to probe your activities, though) – and the chronology is not insignificant either: formed in 2019 as a World Federation of Advertisers (WFA) initiative, partnered with the Association of National Advertisers (ANA).

Then came another “partnership” – that with WEF (World Economic Forum), specifically, its Shaping the Future of Media, Entertainment, and Sport project – a “flagship” one.

In May 2023, the US House Judiciary Committee wanted to know what exactly was happening here, and whether “brand safety” as a concept, as exercised by these entities, could be linked to censorship of online speech.

So the Committee subpoenaed the World Federation of Advertisers (and GARM), asking for records that might show whether these groups “coordinated efforts to demonetize and censor disfavored speech online.”

Committee Chairman Jim Jordan was at the time concerned that this conduct might have run afoul of US antitrust laws.

For X, despite the strides the platform has made toward protecting users’ speech since the Twitter takeover, the GARM relationship is most likely simply about (ad) money – and one of the several efforts to make the platform profitable at last.

Those who were hoping for a “free speech absolutism” on a platform like this might be disappointed, the Congress might investigate some more; but ultimately, the move represents a “realpolitik-style” compromise.

And so X is “excited” and “proud” to be back as a GARM member. The company’s “Safety” account posted something about “the safety of our global town square” apparently being relevant to this decision, but did not elaborate.

Now listed by GARM along with X are YouTube and Chanel – and, in between, some of the biggest pharma and telecoms out there.

Big Money, one might say.

Corporate legacy media are trying to keep key social platforms “in check” by running stories about them complying – or being complicit, or compatible with – some of the currently most notorious anti-free speech legislation.

Meta’s Oversight Board is thus said to be working to adhere to the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) – but perhaps not as efficiently as it should.

Yet before any entity can execute censorship, it must be funded, since it all eventually, one way or another, comes down to money. In this case, Meta has apparently been increasingly less enthusiastic about providing that money.

But now, the Board appears to be looking at the DSA as an avenue to get the money, so that “the mission” may continue.

This sum-up of the seemingly muddled train-of-thought reporting comes from the Washington Post – but the key point behind it seems to be closer to home in the US, than anything that may or may not be happening in Europe.

Meta’s Board was first conceived in 2018 – as the corporation was still trying to fight off (what turned out to be debunked) accusations that it allowed foreign propaganda to fully steer US elections, two years prior.

Facebook (Meta) was happy to establish the Board – and in the process essentially agreed with the 2016 election integrity deniers who claimed it was something other than the majority vote cast by US citizens who decided the outcome.

Meta may have done it just to get rabid politicians and media off their back – but in the meantime, it looks like the company lost the will to keep spending money on the Board.

Now, with another election coming up, the same media are criticizing the Board as having failed their expectations in the US – but they still want it there, and the EU might provide the financial lifeline.

The Washington Post calls it nothing short of the Oversight Board possibly getting “a second chance.” To do what?

Apparently, let a “court of journalists, analysts and experts (…) investigate Meta’s handling of controversial posts” – and reinstate Facebook to its supposedly existing pre-2016 glory (restore “Meta’s blemished reputation,” as WaPo puts it).

Now, the EU comes into the picture, and the DSA is a possible new “funding factor.”

“The Oversight Board administrators touted (to the EU) the group’s experience in making impartial decisions about contentious content moderation challenges facing Meta, according to a slide-deck pitch, which was viewed by the Washington Post,” said the report.

We now live in a world where “fact-checkers” organize “annual meetings” – one is happening just this week in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

These censorship-overseers for other companies (most notably massive social platforms like Facebook, etc.) have not only converged onto Sarajevo but have issued a “statement” that includes the town’s name.

The Poynter Institute is a major player in this space, and its International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN) serves to coordinate censorship for Meta, among others.

It was up to IFCN now to issue the “Sarajevo statement” on behalf of 130 groups in the “fact-checking” business, a burgeoning industry at this point spreading its tentacles to at least 80 countries – that is how many are behind the said statement.

No surprise, these “fact-checkers” like themselves, and see nothing wrong with what they do; the self-affirming statement refers to the (Poynter-led) brand of “fact-checking” as essential to free speech (will someone fact-check that statement, though?)

The reason the focus is on free speech is clear – “fact-checkers” have over and over again proven themselves to be either inept, biased, serving as tools of censorship, all three, or some combination of those.

That is why their “annual meeting” now declares, with a seemingly straight face, that “fact-checking” is not only a free-speech advocate but “should never be considered a form of censorship.”

But who’s going to tell Meta? In the wake of the 2016 US presidential elections, Facebook basically became the fall guy picked by those who didn’t like the outcome of the vote, accusing the platform of being the place where a (since debunked) massive “misinformation meddling campaign” happened.

Aware of the consequences its business might suffer if such a perceived image continued, Facebook by 2019, just ahead of another election, had as many as 50 “fact-checking” partners, “reviewing and rating” content.

In 2019, reports were clearly spelling out how the thing works – it’s in stark contrast with the “Sarajevo statement” and the “… never censorship…” claim.

And this is how it worked: “Fact-checked” posts are automatically marked on Facebook, and videos that have been rated as “false” are still shareable but are shown lower in news feeds by Facebook’s algorithm.

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg has also said that warning labels on posts curb the number of shares by 95%.

“We work with independent fact-checkers. Since the COVID outbreak, they have issued 7,500 notices of misinformation which has led to us issuing 50 million warning labels on posts. We know these are effective because 95% of the time, users don’t click through to the content with a warning label,” Zuckerberg revealed.

That was before the 2020 vote. There is not one reason to believe that, if things have in the meanwhile changed, they have changed for the better – at least where free speech is concerned.

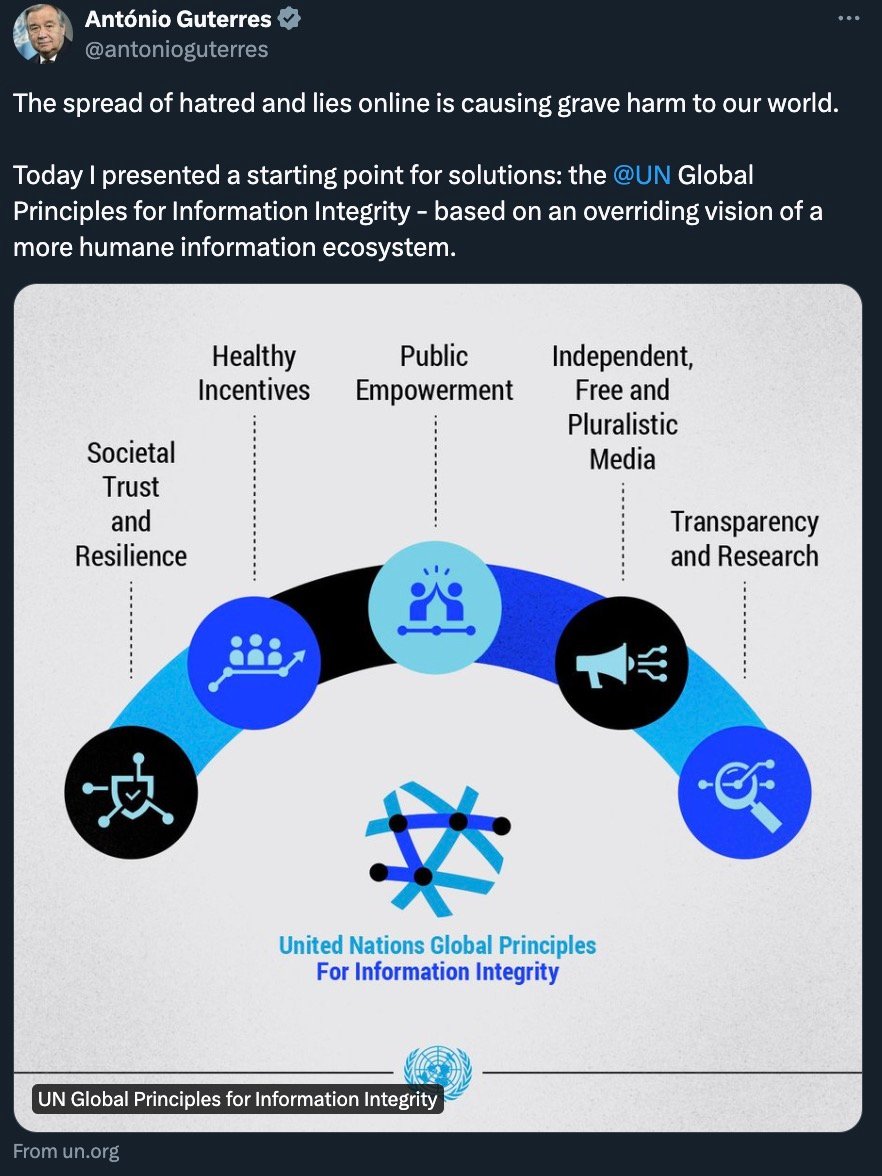

The United Nations has unveiled the latest in a series of censorship initiatives, this one dubbed, the Global Principles for Information Integrity.

Neither the problems nor the solutions, as identified by the principles, are anything new; rather, they sound like regurgitated narratives heard from various nation-states, only this time lent the supposed clout of the UN and its chief, Antonio Guterres.

The topic is, “harm from misinformation and disinformation, and hate speech” – and this is presented with a sense of urgency, calling for immediate action from, once again, the usual group of entities that are supposed to execute censorship: governments, tech companies, media, advertisers, PR firms.

They are at once asked not to use or amplify “disinformation and hate speech” and then also combat it with some tried-and-tested tools: essentially algorithm manipulation (by “limiting algorithmic amplification”), labeling content, and the UN did not stop short of recommending demonetizing the “offenders.”

Presenting the plan on Monday, Guterres made the obligatory mention of doing all that while “at the same time upholding human rights such as freedom of speech.”

According to the UN secretary-general, billions of people are currently in grave danger due to exposure to lies and false narratives (but he doesn’t specify what kind). However, that becomes fairly clear as he goes on to mention that action is needed to “safeguard democracy, human rights, public health, and climate action.”

Guterres also spoke about alleged conspiracy theories and a “tsunami of falsehoods” that he asserts are putting UN peacekeepers at risk.

This is interesting not only because of the tone and narrative the UN chief chose to go with but also as a reminder that peacekeeping, rather than policing social platforms and online speech, used to be one of the UN’s primary reasons for existing and spending money member-countries taxpayer money.

Guterres revealed that the principles stand against algorithms deciding what people see online (another attack on YouTube, etc., recommendations system, for all the wrong reasons?). But he reassures his audience the idea is to “prioritize safety and privacy over advertising,” i.e., profit.

The next thing Guterres wants these decidedly for-profit behemoths, including advertisers, to do is make sure tech companies keep them abreast so as not to “end up inadvertently funding disinformation or hateful messaging.”

According to him, the principles are there to “empower people to demand their rights, help protect children, ensure honest and trustworthy information for young people, and enable public interest-based media to convey reliable and accurate information.”

The US Supreme Court has ruled in the hotly-awaited decision for the Murthy v. Missouri case, reinforcing the government's ability to engage with social media companies concerning the removal of speech about COVID-19 and more. This decision reverses the findings of two lower courts that these actions infringe upon First Amendment rights.

The opinion, decided by a 6-3 vote, found that the plaintiffs, lacked the standing to sue the Biden administration. The dissenting opinions came from conservative justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, and Neil Gorsuch.

We obtained a copy of the ruling for you here.

John Vecchione, Senior Litigation Counsel at NCLA, responded to the ruling, telling Reclaim The Net, "The majority of the Supreme Court has declared open season on Americans' free speech rights on the internet," referring to the decision as an "ukase" that permits the federal government to influence third-party platforms to silence dissenting voices. Vecchione accused the Court of ignoring evidence and abdicating its responsibility to hold the government accountable for its actions that crush free speech. "The Government can press third parties to silence you, but the Supreme Court will not find you have standing to complain about it absent them referring to you by name apparently. This is a bad day for the First Amendment," he added.

Jenin Younes, another Litigation Counsel at NCLA, echoed Vecchione's sentiments, labeling the decision a "travesty for the First Amendment" and a setback for the pursuit of scientific knowledge. "The Court has green-lighted the government's unprecedented censorship regime," Younes commented, reflecting concerns that the ruling might stifle expert voices on crucial public health and policy issues.

Here is the content converted to Markdown:

Further expressing the gravity of the situation, Dr. Jayanta Bhattacharya, a client of NCLA and a professor at Stanford University, criticized the Biden Administration's regulatory actions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dr. Bhattacharya argued that these actions led to "irrational policies" and noted, "Free speech is essential to science, to public health, and to good health." He called for congressional action and a public movement to restore and protect free speech rights in America.

This ruling comes as a setback to efforts supported by many who argue that the administration, together with federal agencies, is pushing social media platforms to suppress voices by labeling their content as misinformation.

Previously, a judge in Louisiana had criticized the federal agencies for acting like an Orwellian "Ministry of Truth." However, during the Supreme Court's oral arguments, it was argued by the government that their requests for social media platforms to address "misinformation" more rigorously did not constitute threats or imply any legal repercussions – despite the looming threat of antitrust action against Big Tech.

Here are the key points and specific quotes from the decision:

Lack of Article III Standing: The Supreme Court held that neither the individual nor the state plaintiffs established the necessary standing to seek an injunction against government defendants. The decision emphasizes the fundamental requirement of a "case or controversy" under Article III, which necessitates that plaintiffs demonstrate an injury that is "concrete, particularized, and actual or imminent; fairly traceable to the challenged action; and redressable by a favorable ruling" (Clapper v. Amnesty Int'l USA, 568 U. S. 398, 409).

Inadequate Traceability and Future Harm: The plaintiffs failed to convincingly link past social media restrictions and government communications with the platforms. The decision critiques the Fifth Circuit's approach, noting that the evidence did not conclusively show that government actions directly caused the platforms' moderation decisions. The Court pointed out: "Because standing is not dispensed in gross, plaintiffs must demonstrate standing for each claim they press" against each defendant, "and for each form of relief they seek" (TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez, 594 U. S. 413, 431). The complexity arises because the platforms had "independent incentives to moderate content and often exercised their own judgment."

Absence of Direct Causation: The Court noted that the platforms began suppressing COVID-19 content before the defendants' challenged communications began, indicating a lack of direct government coercion: "Complicating the plaintiffs' effort to demonstrate that each platform acted due to Government coercion, rather than its own judgment, is the fact that the platforms began to suppress the plaintiffs' COVID–19 content before the defendants' challenged communications started."

Redressability and Ongoing Harm: The plaintiffs argued they suffered from ongoing censorship, but the Court found this unpersuasive. The platforms continued their moderation practices even as government communication subsided, suggesting that future government actions were unlikely to alter these practices: "Without evidence of continued pressure from the defendants, the platforms remain free to enforce, or not to enforce, their policies—even those tainted by initial governmental coercion."

"Right to Listen" Theory Rejected: The Court rejected the plaintiffs' "right to listen" argument, stating that the First Amendment interest in receiving information does not automatically confer standing to challenge someone else's censorship: "While the Court has recognized a 'First Amendment right to receive information and ideas,' the Court has identified a cognizable injury only where the listener has a concrete, specific connection to the speaker."

Justice Alito's dissent argues that the First Amendment was violated by the actions of federal officials. He contends that these officials coerced social media platforms, like Facebook, to suppress certain viewpoints about COVID-19, which constituted unconstitutional censorship. Alito emphasizes that the government cannot use coercion to suppress speech and points out that this violates the core principles of the First Amendment, which is meant to protect free speech, especially speech that is essential to democratic self-government and public discourse on significant issues like public health.

Here are the key points of Justice Alito's stance:

Extensive Government Coercion: Alito describes a "far-reaching and widespread censorship campaign" by high-ranking officials, which he sees as a serious threat to free speech, asserting that these actions went beyond mere suggestion or influence into the realm of coercion. He states, "This is one of the most important free speech cases to reach this Court in years."

Impact on Plaintiffs: The dissent underscores that this government coercion affected various plaintiffs, including public health officials from states, medical professors, and others who wished to share views divergent from mainstream COVID-19 narratives. Alito notes, "Victims of the campaign perceived by the lower courts brought this action to ensure that the Government did not continue to coerce social media platforms to suppress speech."

Legal Analysis: Alito criticizes the majority's dismissal based on standing, arguing that the plaintiffs demonstrated both past and ongoing injuries caused by the government's actions, which were likely to continue without court intervention. He argues, "These past and threatened future injuries were caused by and traceable to censorship that the officials coerced."

Evidence of Coercion: The dissent points out specific instances where government officials pressured Facebook, suggesting significant consequences if the platform failed to comply with their demands to control misinformation. This included threats related to antitrust actions and other regulatory measures. Alito highlights, "Not surprisingly, these efforts bore fruit. Facebook adopted new rules that better conformed to the officials' wishes."

Potential for Future Abuse: Alito warns of the dangerous precedent set by the Court's refusal to address these issues, suggesting that it could empower future government officials to manipulate public discourse covertly. He cautions, "The Court, however, shirks that duty and thus permits the successful campaign of coercion in this case to stand as an attractive model for future officials who want to control what the people say, hear, and think."

Importance of Free Speech: He emphasizes the critical role of free speech in a democratic society, particularly for speech about public health and safety during the pandemic, and criticizes the government's efforts to suppress such speech through third parties like social media platforms. Alito asserts, "Freedom of speech serves many valuable purposes, but its most important role is protection of speech that is essential to democratic self-government."

The case revolved around allegations that the federal government, led by figures such as Dr. Vivek Murthy, the US Surgeon General, (though also lots more Biden administration officials) colluded with major technology companies to suppress speech on social media platforms. The plaintiffs argue that this collaboration targeted content labeled as "misinformation," particularly concerning COVID-19 and political matters, effectively silencing dissenting voices.

The plaintiffs claim that this coordination represents a direct violation of their First Amendment rights. They argue that while private companies can set their own content policies, government pressure that leads to the suppression of lawful speech constitutes unconstitutional censorship by proxy.

The government's campaign against what it called "misinformation," particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic – regardless of whether online statements turned out to be true or not – has been extensive.

However, Murthy v. Missouri exposed a darker side to these initiatives—where government officials allegedly overstepped their bounds by coercing tech companies to silence specific narratives.

Communications presented in court, including emails and meeting records, suggest a troubling pattern: government officials not only requested but demanded that tech companies remove or restrict certain content. The tone and content of these communications often implied serious consequences for non-compliance, raising questions about the extent to which these actions were voluntary versus compelled.

Tech companies like Facebook, Twitter, and Google have become the de facto public squares of the modern era, wielding immense power over what information is accessible to the public. Their content moderation policies, while designed to combat harmful content, have also been criticized for their lack of transparency and potential biases.

In this case, plaintiffs argued that these companies, under significant government pressure, went beyond their standard moderation practices. They allegedly engaged in the removal, suppression, and demotion of content that, although controversial, was not illegal. This raises a critical issue: the thin line between moderation and censorship, especially when influenced by government directives.

The Supreme Court ruling holds significant implications for the relationship between government actions and private social media platforms, as well as for the legal frameworks that govern free speech and content moderation.

Here are some of the broader impacts this ruling may have:

Clarification on Government Influence and Private Action: This decision clearly delineates the limits of government involvement in the content moderation practices of private social media platforms. It underscores that mere governmental encouragement or indirect pressure does not transform private content moderation into state action. This ruling could make it more challenging for future plaintiffs to claim that content moderation decisions, influenced indirectly by government suggestions or pressures, are tantamount to governmental censorship.

Stricter Standards for Proving Standing: The Supreme Court's emphasis on the necessity of concrete and particularized injuries directly traceable to the challenged government action sets a high bar for future litigants. Plaintiffs must now provide clear evidence that directly links government actions to the moderation practices that allegedly infringe on their speech rights. This could lead to fewer successful challenges against perceived government-induced censorship on digital platforms.

Impact on Content Moderation Policies: Social media platforms may feel more secure in enforcing their content moderation policies without fear of being seen as conduits for state action, as long as their decisions can be justified as independent from direct government coercion. This could lead to more assertive actions by platforms in moderating content deemed harmful or misleading, especially in critical areas like public health and election integrity.

Influence on Public Discourse: By affirming the autonomy of social media platforms in content moderation, the ruling potentially influences the nature of public discourse on these platforms. While platforms may continue to engage with government entities on issues like misinformation, they might do so with greater caution and transparency to avoid allegations of government coercion.

Future Legal Challenges and Policy Discussions: The ruling could prompt legislative responses, as policymakers may seek to address perceived gaps between government interests in combating misinformation and the protection of free speech on digital platforms. This may lead to new laws or regulations that more explicitly define the boundaries of acceptable government interaction with private companies in managing online content.

Broader Implications for Digital Rights and Privacy: The decision might also influence how digital rights and privacy are perceived and protected, particularly regarding how data from social media platforms is used or shared with government entities. This could lead to heightened scrutiny and potentially stricter guidelines to protect user data from being used in ways that could impinge on personal freedoms.

Overall, the Murthy v. Missouri ruling will likely serve as a critical reference point in ongoing debates about the government's ability to influence and shut down speech.

The Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD), a UK think tank that was in 2021 awarded a grant by the US State Department and got involved in censoring Americans, has come up with a “research project” that criticizes YouTube.

The target is the platform’s recommendation algorithms, and, according to ISD – which calls itself an extremism researching non-profit – there is a “pattern of recommending right-leaning and Christian videos.”

According to ISD, this is true even if users had not previously watched this type of content.

YouTube’s recommendation system has long been a thorn in the side of similar liberal-oriented groups and media, as apparently that one segment of the giant site that’s not yet “properly” controlled and censored.

With that in mind, it is no surprise that ISD is now producing a four-part “study” and offering its own “recommendations” on how to mend the situation they disfavor.

The group went for creating mock user accounts designed to pretend to be interested in gaming, what ISD calls male lifestyle gurus, mommy vloggers, as well as news in Spanish.

The “personas” built in this way received recommendations on what to watch next that seems to suggest Google video platform’s algorithms are doing what they were built to do – identifying users’ interests and keeping them in that loop.

For example, the account that watched Joe Rogan and Jordan Peterson (those would be, “male lifestyle gurus”) got Fox News videos suggested as their next watch.

Another result was that accounts representing “mommy vloggers” but with different political orientations got recommendations in line with that – except ISD complains its personas (built in five days, and then recording recommendations for one month) basically, weren’t kept in the echo chamber tightly enough.

“Despite having watched their respective channels for equal amounts of time, the right-leaning account was later more frequently recommended Fox News than the left-leaning account was recommended MSNBC,” the group said.

More complaints concern YouTube surfacing “health misinformation and other problematic content.” And then there are ISD’s demands of YouTube: increase “moderation” of gaming videos, while giving moderators “updated flags about harmful themes appearing in gaming videos.”

As for more aggressively censoring what is considered health misinformation, the demand is to “consistently enforce health misinformation policy.”

Not only that, but ISD wants YouTube to add new terms to that policy regarding when content gets removed or deleted.

This “update” should come by “creating a definitive upper bound of violations could make enforcement of the policy easier and more consistent,” said ISD.

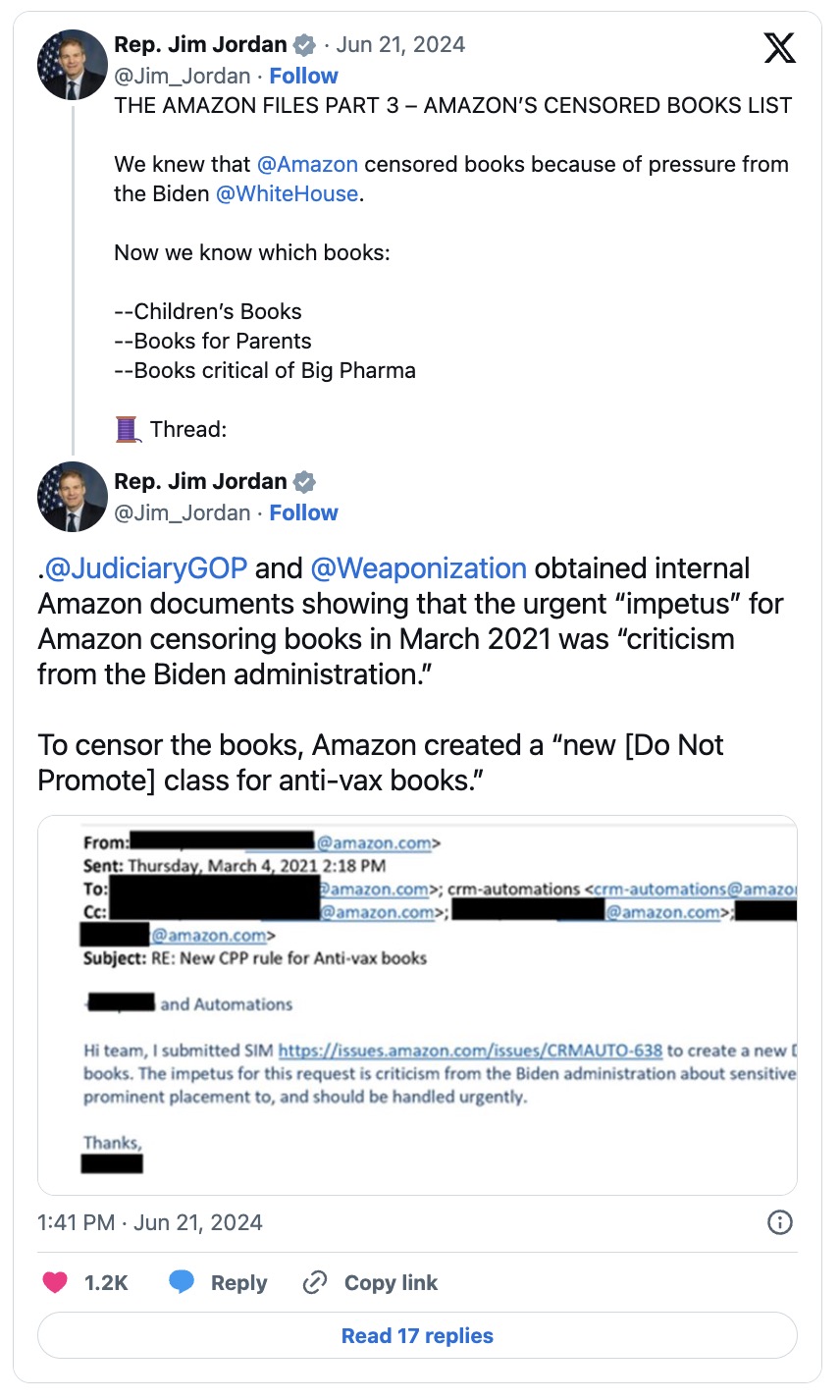

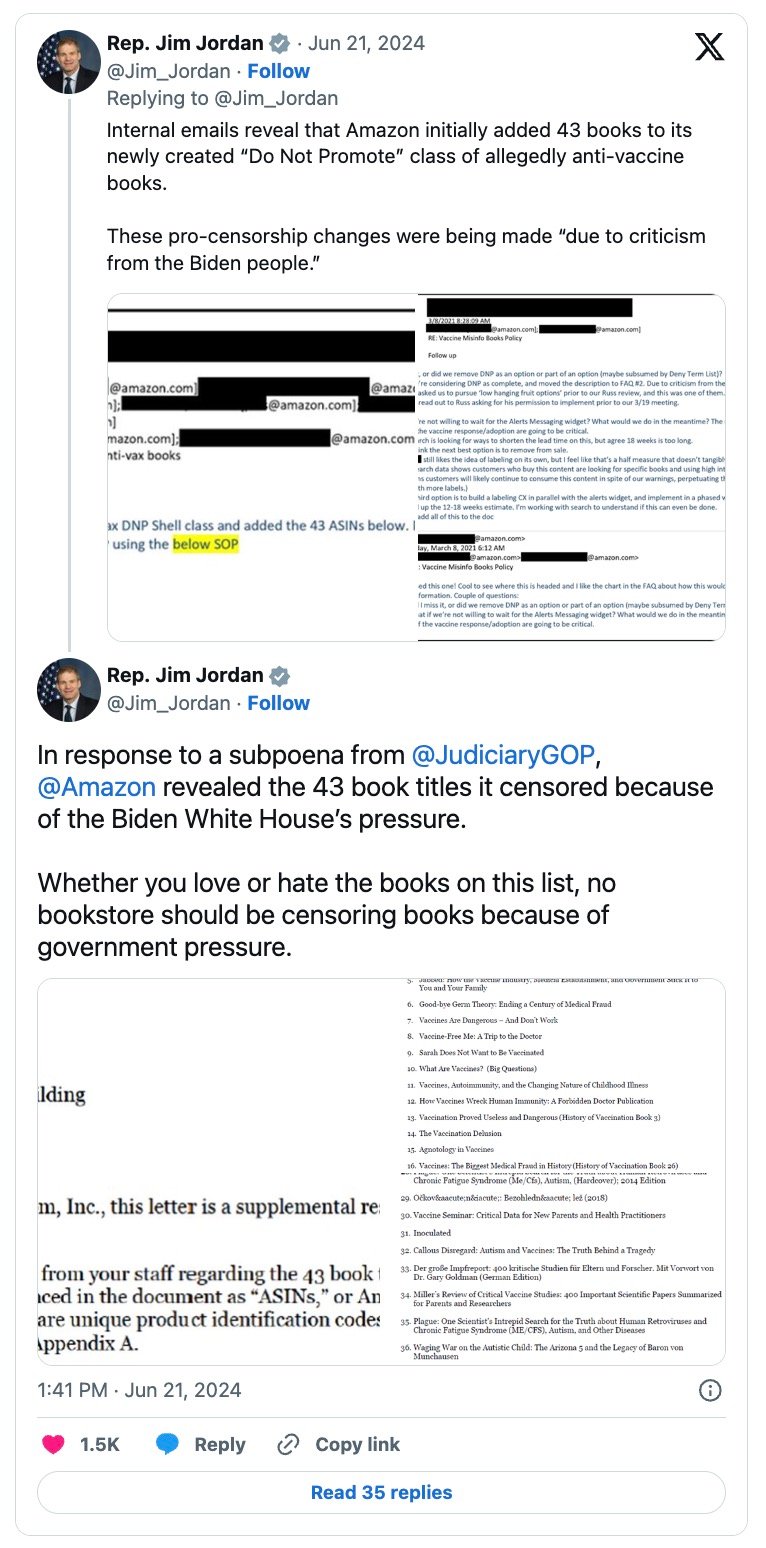

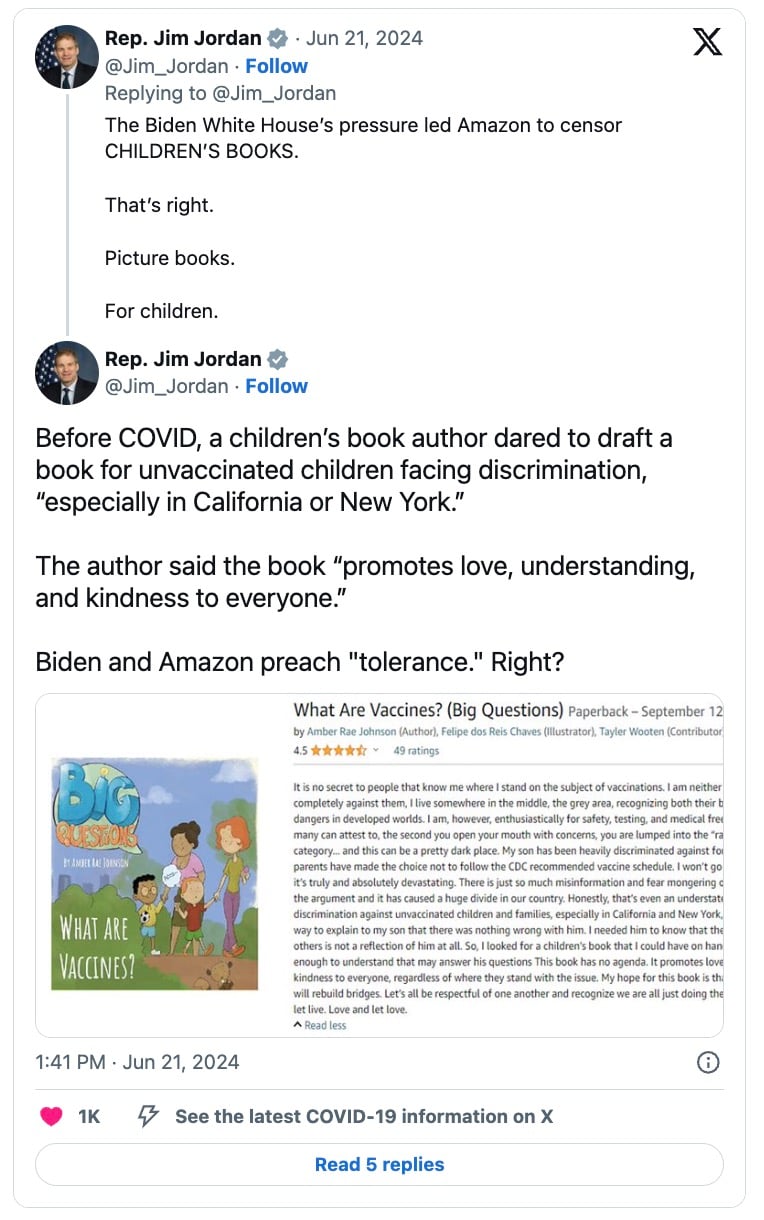

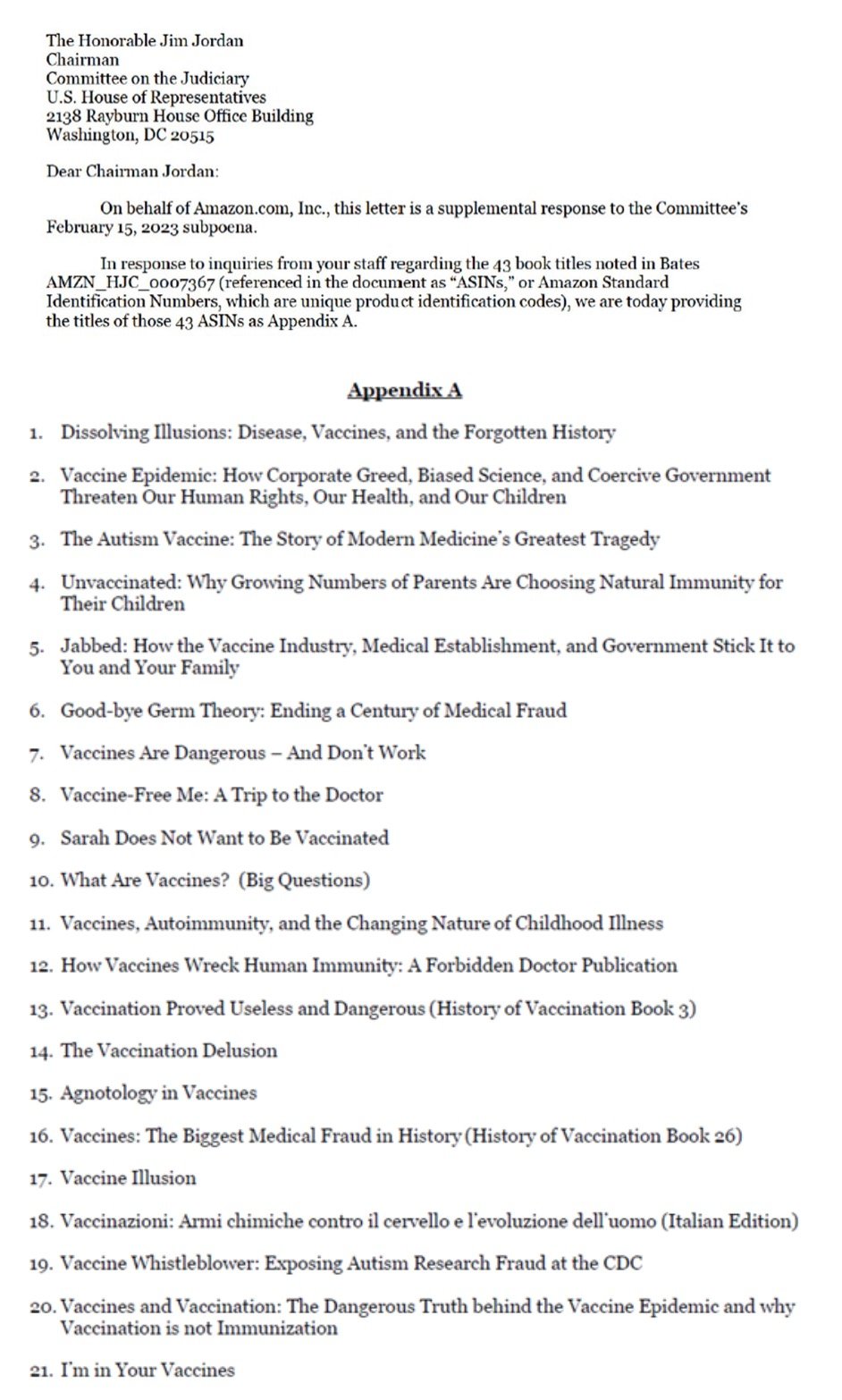

Amazon has been accused of censoring books criticizing vaccines and pharmaceutical practices, following direct pressure from the Biden administration, according to documents obtained by the House Judiciary Committee and the Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government. Representative Jim Jordan, chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, disclosed these actions as part of an investigation into what he describes as “unconstitutional government censorship.”

Internal communications from Amazon have surfaced showing the creation of a new category titled “Do Not Promote,” where over 40 titles, including children’s books and scientific critiques, were placed to minimize their exposure.

This move came after criticisms from the Biden administration concerning the prominent placement of sensitive content on Amazon’s platform. Books in this category addressed controversial topics, such as what some believe is the connection between vaccines and autism, and the financial influence of pharmaceutical companies on scientific research.

Among the suppressed titles were “The Autism Vaccine: The Story of Modern Medicine’s Greatest Tragedy” by Forrest Maready and a parenting book by Dr. Robert Sears that challenges mainstream medical advice on vaccinations.

Rep. Jordan highlighted the broader implications of this censorship, stating, “This is not just about vaccine criticism; it’s a systemic campaign to silence dissenting voices under the guise of combating misinformation.”

Jordan called the administration’s efforts a violation of free speech principles, emphasizing that “free speech is free speech,” regardless of the content. The ongoing commitment by the House Judiciary Republicans and the Weaponization Committee aims to challenge these tactics and ensure the protection of free expression through legislative actions.

Rishi Sunak, the British Prime Minister, recently shocked the nation with a proposal reminiscent of social credit systems for the United Kingdom. The plan suggested restricting access to essential modern conveniences, like cars and financial services, for young individuals refusing to participate in National Service.

During a Thursday night national television forum, electoral party heads fielded audience questions on a BBC-hosted program.

Sunak found himself defending a novel electoral promise – the introduction of mandatory national service for British youths if he could retain his seat. Despite bleak poll evaluations and mounting public pressure, Sunak refused to accept the possibility of defeat.

The Prime Minister utilized the case of a volunteer ambulance service to illustrate potential forms of obligated volunteering. Nonetheless, the public’s worry and debates have predominantly revolved around the compulsory military aspect of National Service.

Sunak, however, sidestepped elaborating on how the government plans to coerce young individuals into the service, seemingly caught off guard when questioned directly about the compulsory factor. He hinted at the possibility of curtailing rights to essential modern living components, while conveniently passing the buck onto an unspecified “independent body.”

The Prime Minister did clarify that options were being evaluated following various European models, which might include restrictions on obtaining driving licenses and access to finance. Despite this, when questioned about the possibility of young individuals having their bank cards revoked for service refusal, he dismissed the suggestion laughingly, providing a negative reply.

“You will have a set of sanctions and incentives and we will look at the models that are existing in Europe to get the appropriate mix of those, there is a range of different options that exist… whether that’s looking at driving licenses, access to finance…” Sunak said.

This approach of using financial penalties and restrictions as a tool for enforcement is not new and has been gaining traction globally. The concept of a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) could potentially simplify the implementation of such policies. A CBDC would provide governments with unprecedented control over the financial system, including the ability to directly enforce financial sanctions against individuals.

However, the use of financial controls to enforce government policies raises significant concerns regarding civil liberties. A prominent example is the actions taken by Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau during the trucker protests in Canada. Trudeau invoked the Emergencies Act to freeze the bank accounts of civil liberties protesters.

In a statement issued on the occasion of the “International Day for Countering Hate Speech,” UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called for the global eradication of so-called “hate speech,” which he described as inherently toxic and entirely intolerable.

The issue of censoring “hate speech” stirs significant controversy, primarily due to the nebulous and subjective nature of its definition. At the heart of the debate is a profound concern: whoever defines what constitutes hate speech essentially holds the power to determine the limits of free expression.

This power, wielded without stringent checks and balances, leads to excessive censorship and suppression of dissenting voices, which is antithetical to the principles of a democratic society.

Guterres highlighted the historic and ongoing damage caused by hate speech, citing devastating examples such as Nazi Germany, Rwanda, and Bosnia to suggest that speech leads to violence and even crimes against humanity.

“Hate speech is a marker of discrimination, abuse, violence, conflict, and even crimes against humanity. We have time and again seen this play out from Nazi Germany to Rwanda, Bosnia and beyond. There is no acceptable level of hate speech; we must all work to eradicate it completely,” Guterres said.

Guterres also noted what he suggested are the worrying rise of antisemitic and anti-Muslim sentiments, which are being propagated both online and by prominent figures.

Guterres argued that countries are legally bound by international law to combat incitement to hatred while simultaneously fostering diversity and mutual respect. He urged nations to uphold these legal commitments and to take action that both prevents hate speech and safeguards free expression.

The UN General Assembly marked June 18 as the “International Day for Countering Hate Speech” in 2021.

Guterres has long promoted online censorship, complaining about the issue of online “misinformation” several times, describing it as “grave” and suggesting the creation of an international code to tackle it.

His strategy involves a partnership among governments, tech giants, and civil society to curb the spread of “false” information on social media, despite risks to free speech.

If it looks like a duck… and in particular, quacks like a duck, it’s highly likely a duck. And so, even though the Stanford Internet Observatory is reportedly getting dissolved, the University of Washington’s Center for an Informed Public (CIP) continues its activities. But that’s not all.

CIP headed the pro-censorship coalitions the Election Integrity Partnership (EIP) and the Virality Project with the Stanford Internet Observatory, while the Stanford outfit was set up shortly before the 2020 vote with the goal of “researching misinformation.”

The groups led by both universities would publish their findings in real-time, no doubt, for maximum and immediate impact on voters. For some, what that impact may have been, or was meant to be, requires research and a study of its own. Many, on the other hand, are sure it targeted them.

So much so that the US House Judiciary Committee’s Weaponization Select Subcommittee established that EIP collaborated with federal officials and social platforms, in violation of free speech protections.

What has also been revealed is that CIP co-founder and leader is one Kate Starbird – who, as it turned out from ongoing censorship and speech-based legal cases, was once a secret adviser to Big Tech regarding “content moderation policies.”

Considering how that “moderation” was carried out, namely, how it morphed into unprecedented censorship, anyone involved should be considered discredited enough not to try the same this November.

However, even as SIO is shutting down, reports say those associated with its ideas intend to continue tackling what Starbird calls online rumors and disinformation. Moreover, she claims that this work has been ongoing “for over a decade” – apparently implying that these activities are not related to the two past, and one upcoming hotly contested elections.

And yet – “We are currently conducting and plan to continue our ‘rapid’ research — working to identify and rapidly communicate about emergent rumors — during the 2024 election,” Starbird is quoted as stating in an email.

Not only is Starbird not ready to stand down in her crusade against online speech, but reports don’t seem to be able to confirm that the Stanford group is actually getting disbanded, with some referring to the goings on as SIO “effectively” shutting down.

What might be happening is the Stanford Internet Observatory (CIP) becoming a part of Stanford’s Cyber Policy Center. Could the duck just be covering its tracks?

Some might see US Attorney General Merrick Garland getting quite involved in campaigning ahead of the November election – albeit indirectly so, as a public servant whose primary concern is supposedly how to keep Department of Justice (DoJ) staff “safe.”

And, in the process, he brings up “conspiracy theorists” branding them as undermining the judicial process in the US – because they dare question the validity of a particular judicial process that aimed at former President Trump.

In an opinion piece published by the Washington Post, Garland used one instance that saw a man convicted for threatening a local FBI office to draw blanket and dramatic conclusions that DoJ staff have never operated in a more dangerous environment, where “threats of violence have become routine.”

It all circles back to the election, and Garland makes little effort to present himself as neutral. Other than “conspiracy theories,” his definition of a threat are calls to defund the department that was responsible for going after the former president.

Ironically, while the tone of his op-ed and the topics and examples he chooses to demonstrate his own bias, Garland goes after those who claim that DoJ is politicized with the goal of influencing the election.

The attorney general goes on to quote “media reports” – he doesn’t say which, but one can assume those following the same political line – which are essentially (not his words) hyping up their audiences to expect more “threats.”

“Media reports indicate there is an ongoing effort to ramp up these attacks against the Justice Department, its work and its employees,” is how Garland put it.

And he pledged that, “we will not be intimidated” by these by-and-large nebulous “threats,” with the rhetoric at that point in the article ramped up to refer to this as, “attacks.”

Garland’s opinion piece is not the only attempt by the DoJ to absolve itself of accusations of acting in a partisan way, instead of serving the interests of the public as a whole.

Thus, Assistant Attorney General Carlos Uriarte wrote to House Republicans, specifically House Judiciary Chairman Jim Jordan, to accuse him of making “completely baseless” accusations against DoJ for orchestrating the New York trial of Donald Trump.

While, as it were, protesting too much, (CNBC called it “the fiery reply”) – Uriarte also went for the “conspiracy theory conspiracy theory”:

“The conspiracy theory that the recent jury verdict in New York state court was somehow controlled by the Department is not only false, it is irresponsible,” he wrote.

Garland and FBI Director Chris Wray recently discussed plans to counter election threats during a DoJ Election Threats Task Force meeting. Critics, suspicious of the timing with the upcoming election, cite the recent disbandment of the DHS Intelligence Experts Group.

Various elections are not the only thing Big Tech is “protecting” this summer: athletes competing in major sporting events are another.

Meta has announced that the “protection measures” that are to affect its apps (Facebook, Instagram, and, Threads) will also extend to the fans.

Regardless of the way Meta phrases it, the objective is clearly to censor what the giant decides is abusive behavior, bullying, and hate speech.

The events that draw Meta’s particular attention are the European football championship (EURO 2024), and the Olympic and Paralympic Games.

To prove how serious it is about implementing censorship in general, the company revealed an investment exceeding $20 billion that went into the “safety and security” segment (often resulting in unrestrained stifling of speech and deplatforming.)

Coincidentally or not, this investment began in 2016, and since then, what Meta calls its safety and security team went up to 40,000 members, with 15,000 used as “content reviewers.”

Before explaining how it’s going to “keep athletes and fans safe,” Meta also summed up the result of this spending and activities: 95% of whatever was deemed to be “hate speech” and similar has been censored before it even got reported, whereas some component of AI was used to automate issuing warnings to users that their comments “might be offensive.”

Now, Meta says that users will be allowed to turn off DM requests on Instagram, isolating themselves in this way from anyone they don’t follow. This is supposed to “protect” athletes presumably from unhappy fans, and there’s also “Hidden Words.”

“When turned on, this feature automatically sends DM requests — including Story replies — containing offensive words, phrases and emojis to a hidden folder so you don’t have to see them,” the blog post explained, adding, “It also hides comments with these terms under your posts.”

This is just one of the features on Facebook and Instagram that effectively allows people to use these platforms for influence and/or monetary gain, but without interacting with anyone they don’t follow, including indirectly via comments (that will be censored, aka, “moderated”).

Meta is not only out to “protect athletes,” but “educate” other users, this time on how to display “supportive behavior.” It doesn’t bode well that notoriously error-prone algorithms (AI) seem to have been given a key role in detecting “abusive” or “offensive” comments and then warning people they “may be breaking our rules.”

But this “training of users” works, according to Meta, that shared testing of what they refer to as interventions showed that “people edited or deleted their comment 50% of the time after seeing these warnings.”

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau last week complained that governments have allegedly been left without the necessary tools to “protect people from misinformation.”

This “dire” warning came as part of Trudeau’s effort to have the Online Harms Act (Bill C-63) – one of the most controversial of its kind pieces of censorship legislation in Canada of late – pushed across the finish line in the country’s parliament.

C-63 has gained notoriety among civil rights and privacy advocates because of some of its provisions around “hate speech,” “hate propaganda,” and “hate crime.”

Under the first two, people would be punished before they commit any transgression, but also retroactively.

However, in a podcast interview for the New York Times, Trudeau defended C-63 as a solution to the “hate speech” problem, and clearly, a necessary “tool,” since according to this politician, other avenues to battle real or imagined hate speech and crimes resulting from it online have been exhausted.

Not one to balk at speaking out of both sides of his mouth, Trudeau at one point essentially admits that the more control governments have (and the bill is all about control, critics say, regardless of how its sponsors try to sugarcoat it) the more likely they are to abuse it.

He nevertheless goes on to declare that new legislative methods of “protecting people from misinformation” are needed and, in line with this, talk up C-63 as some sort of balanced approach to the problem.

But it’s difficult to see that “balance” in C-63, which is currently debated in the House of Commons. If it becomes law, it will allow the authorities to keep people under house arrest should they decide these people could somewhere down the line commit “hate crime or hate propaganda” – a chilling application of the concept of “pre-crime.”

These persons could also be banned from accessing the internet.

The bill seeks to not only produce a new law but also amend the Criminal Code and the Canadian Human Rights Act, and one of the provisions is no less than life in prison for those found to have committed a hate crime offense along with another criminal act.

As for hate speech, people whose statements run afoul of C-63 would face fines equivalent to some $51,000.